Although it was the natural next step in my bid for the seven summits, climbing Denali proved to be an altogether different beast

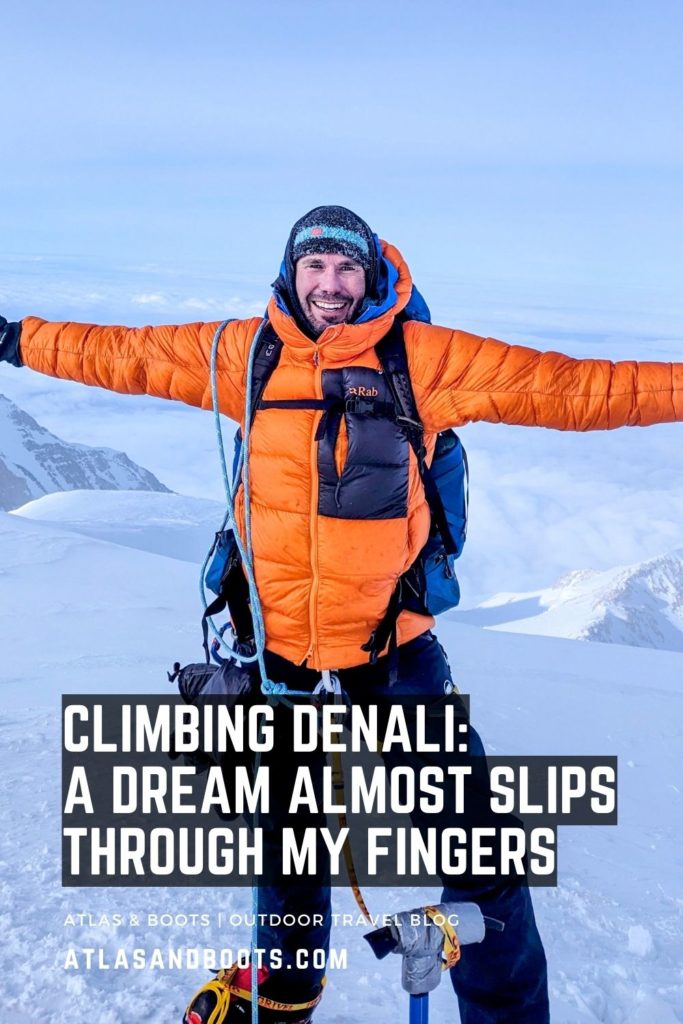

At around 6.30pm local time on Tuesday 28 May 2024, six grown men stood on the summit of Denali, the highest peak in North America, crying their eyes out. Among us was a triathlon athlete, a veteran of the Marathon des Sables and an Everest summiteer returning to Denali for his second attempt. One of our group, a Californian who regularly climbed in the Sierras, was on his knees sobbing over his ice axe. I tried to record a video message for Instagram but couldn’t speak through my tears of relief

Climbing Denali is the hardest thing I have ever done. I trained for over a year, spent a fortune on the expedition and then almost let it slip through my fingers at the final hurdle. For me, Denali was a one-time shot. I couldn’t afford to come back to this monstrosity of a mountain so giving up on Denali meant giving up on the seven summits.

Fortunately, my seven summit story doesn’t end here. Whether or not I can afford to have a crack at Everest or Vinson is another question but, for now, the improbable dream is still alive. Below is my account of climbing Denali; my journey to the top of North America and my toughest challenge yet.

Climbing Denali contents

- Denali: the tall one

- Climbing Denali itinerary

- Onto the glacier

- Moving up the mountain

- Comings and goings

- The fixed lines

- Summit day

- The descent

- The essentials

Denali: the tall one

At 6,190m (20,310ft), Denali in Alaska, USA, is the highest peak in North America and the third highest mountain of the seven summits. It was my fourth mountain of the seven after Aconcagua in South America, Elbrus in Europe and Kilimanjaro in Africa. I don’t include Kosciuszko in Australia as I subscribe to the ‘Messner List’ which means Kosciuszko is not a seven summit.

Denali is arguably the second hardest mountain of the seven summits. It is an extremely challenging campaign as climbers must carry heavy loads throughout, particularly at the beginning of the expedition where they have to carry a backpack and haul a sledge over a crevasse-strewn glacier. The notoriously stormy, unpredictable and relentlessly cold weather on a mountain located at 63° North – just 3° degrees south of the Arctic Circle – makes it even tougher.

| Continent | The Messner version | The Bass version |

|---|---|---|

| Asia | Everest | Everest |

| South America | Aconcagua | Aconcagua |

| North America | Denali | Denali |

| Africa | Kilimanjaro | Kilimanjaro |

| Europe | Elbrus | Elbrus |

| Antarctica | Vinson | Vinson |

| Oceania | Puncak Jaya (Carstensz Pyramid) | Kosciuszko |

The name Denali comes from Koyukon, a traditional Native Alaskan language, and means ‘the tall one’. The name had been used for generations until 1896 when a gold prospector began referring to the mountain as Mt McKinley after William McKinley, a presidential candidate at the time. After McKinley became president and was later assassinated, Congress formally recognised the name in 1917 even though McKinley had never visited Alaska. After decades of petitioning by the Alaska Legislature, supported by many Alaskans, mountaineers and Alaska Natives, in 2015, President Obama officially changed the name back to Denali.

Climbing Denali itinerary

I spent 19 days climbing Denali via the West Buttress route. My itinerary is below, although it comes with a certain degree of flexibility depending on the conditions on the mountain. There are four additional days built in as reserve days in case of bad weather. We used two of these during our ascent and had two that remained unused.

| Day | From/to | Altitude |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Drive to Talkeetna; fly to Kahiltna Airstrip (base camp) | 2,200m |

| 2 | Move to Camp 1 | 2,350m |

| 3 | Load carry to cache below Camp 2 | 3,000m |

| 4 | Move to Camp 2 | 3,350m |

| 5 | Back carry from below Camp 2 | 3,350m |

| 6 | Rest day at Camp 2 | 3,350m |

| 7 | Load carry to cache around Windy Corner | 4,100m |

| 8 | Move up to Camp 3 | 4,330m |

| 9 | Rest day at Camp 3 (snowed in) | 4,330m |

| 10 | Back carry from Windy Corner | 4,330m |

| 11 | Rest day (hike to ‘End of the World’) | 4,330m |

| 12 | Load carry to cache at the top of the fixed ropes | 4,900m |

| 13 | Rest day at Camp 3 | 4,330m |

| 14 | Move up and establish Camp 4/High Camp | 5,245m |

| 15 | Back carry/rest day at Camp 4/High Camp | 5,245m |

| 16 | Summit day | 6,100m |

| 17 | Descend to Camp 3 | 4,330m |

| 18 | Descend to Kahiltna Airstrip (base camp) | 2,200m |

| 19 | Return flight to Talkeetna | n/a |

| 20 | Contingency day | n/a |

| 21 | Contingency day | n/a |

Onto the glacier

Our team of nine clients and three guides met in Anchorage, Alaska’s biggest city, the day before the expedition to finalise gear and complete some last-minute shopping. The following day we drove two hours north to the tiny frontier town of Talkeetna. Here, we visited the National Park Service ranger station to register our details and receive a short briefing before hopping on a tiny single-engined propeller plane, fitted with skis, for a thrilling 45-minute flight onto the Kahiltna Glacier.

That first afternoon and evening, we set ourselves up at Kahiltna base camp and set about organising our gear and familiarising ourselves with the routines of glacier life. We scraped bases out for tents, dug vestibules into their porches, learnt how to use our Clean Mountain Cans (CMCs) – the portable toilets that we would use to transfer all our human waste off the mountain, organised our gear for the following morning and generally marvelled at the fantastical panoramic views surrounding us.

The first day on the mountain was a day I had been dreading and training for since I first put down my deposit for the expedition. It would be the only day on the mountain when we would be carrying all our gear in what’s known as a ‘single carry’ to Camp 1. When we weighed our gear in Talkeetna, we had 720kg of gear between 12 people – 60kg each. This was split between a sledge (~40kg) and a backpack (~20kg).

Although it was my first time pulling a sledge and my first time moving as a four-person roped team, in the end, my training paid off and the day proved to be manageable. We soon found a rhythm and worked our way along the glacier as it swung around Mt Frances with the peaks of the enormous Mt Foraker and its neighbour Mt Crosson towering over us.

The first part of the ‘climb’ was actually downhill. Heartbreak Hill drops around 175m (575ft) out of base camp. It is so named as its ascent is the final challenge of most expeditions on the mountain. After this, the route gently climbs the glacier towards Camp 1. We had glorious weather that day and were moving in our base layers, struggling to stay cool with the strong sun beating down from above and reflecting off the ice from below.

Seven hours later, we stumbled into Camp 1 – our first day on Denali complete. But the day’s work wasn’t over. As with every new camp, there was work to be done. Pitches had to be levelled, our tents had to be pitched and our vestibules, toilet and mess tent dug out before we could relax for the evening.

Moving up the mountain

The route above Camp 1 was the first serious rise in altitude of the climb and thus required us to wear snowshoes for the first time. To avoid carrying full loads any further up the mountain, we began carrying loads to cache areas around two-thirds of the way between camps to collect later. We packed up all the food, supplies and any personal gear that we would need at the higher camps and began our first ‘load carry’.

After leaving camp, we began ascending Ski Hill – the steepest climb of the route between camps one and two. While the slope is not steep, an (almost) fully-laden sledge makes the going tough, not to mention the hidden crevasses that riddle the slope.

Around halfway up Ski Hill, we had our first major setback. A member of our team had been struggling with nausea and stomach issues and was forced to withdraw from the climb. This meant that he had to be escorted back to base camp immediately to get a plane off the glacier. As we had to travel in rope teams, three members of our team (one guide and two clients) descended with him to base camp. This significantly delayed our progress that day as we had to divide gear and repack sledges while our team split up.

It was a blow to morale to lose our first team member so early on and had knock-on effects for the entire team; for those who would have to return to base camp and back but also for the rest of us who had to take on more load carrying as they left all their non-essential gear. Eventually, we said our goodbyes and continued on our separate ways.

Around two-thirds of the way to Camp 2, we stopped on a flat, open part of the glacier, dug a hole, cached our gear to be collected in a couple of days and marked the spot with some wands. Our sledges empty, we strapped them onto our backs and descended back to Camp 1 on what felt like a hop, skip and a jump compared to the trials of the morning.

The following day, we struck camp and moved up to Camp 2, passing our cache spot en route. It was a long day made harder as we were hauling extra gear left by our teammates who’d descended the previous day. We arrived at Camp 2 after nine hours of climbing, utterly exhausted. However, there was no time to relax as we had the usual camp preparations to make.

Eventually, as the sun slid behind the surrounding peaks and cast the campsite into the shade, we crawled into our tents. We hadn’t managed to get the mess tent dug out so that night we slurped soup and noodles in our tents.

The following day, we had a slow start to the day as it was an ‘active rest day’ meaning we only had to collect our cached gear from below camp, known as a ‘back carry’. It took just 20 minutes to descend to the cache site but around 2.5 hours to haul it back up to Camp 2. We got back late afternoon feeling pretty content knowing that the following day was to be our first full rest day on Denali.

Comings and goings

Shortly after we arrived back in camp after retrieving our cache, our team was reunited as our other three members traipsed into camp. Their journey had seen them retrace their footsteps to base camp. Then, after our teammate had caught a morning flight back to Talkeetna, they returned to Camp 1, stayed overnight and then followed us up to Camp 2. Between their extra footfall and our extra load carrying, we had collectively earned the ensuing rest day.

We spent the day relaxing in our tents, reading, snoozing and eating and drinking. Unfortunately, the day brought more upheaval. One of our team developed frostnip (an early sign of frostbite) in his fingers while another member decided against continuing with the climb. It meant we were to lose another two members of our team. It was decided that one of our guides would escort them off the mountain while we continued to climb.

So the next day, our team once again split up with three members (two clients and a guide) heading down while the rest of us completed a load carry towards Camp 3. It was the first significant increase in altitude. The first hurdle was Motorcycle Hill, a long, steep slog straight out of camp that gains almost 500m.

The route then flattens for a while and leads to a col, from where there are striking views of the North East face. From the col, the route continues up steeply beside rock buttresses to another tough climb called Squirrel Hill. Again, the route flattened out before a series of gradually steepening snow slopes on the approach to the aptly named Windy Corner at the southwest foot of the West Buttress. This natural wind tunnel can create huge storms. Fortunately for us, every time we passed the Corner, the infamous gales were absent. We cached our gear just around the bend on a vast snowfield before turning to Camp 2 for the evening.

The next day, we struck camp and retraced our footsteps and then moved beyond our cache site and past a string of enormous crevasses to Camp 3, the largest and busiest camp on the mountain. There are park rangers stationed at the camp and it functions as the main base for rescues. Climbers on several routes use the camp and those on the West Buttress route tend to stay for several days acclimatising, hence its size. Its location, nestled at the foot of an immense headwall and surrounded by an amphitheatre of saw-toothed ridges and peaks, is spectacular.

Until now, we had enjoyed excellent weather but that all changed almost as soon as we arrived at Camp 3. High winds and snowfall rolled off the slopes above as we built snow walls around our tents. The weather stayed throughout the night and most of the following day, pinning us down in Camp 3 for 24 hours. Reserve days are built into the itinerary for exactly this reason. Besides, after a long day on the mountain, nobody was complaining about an enforced rest day.

By now, the stress of being on an extremely cold mountain was beginning to take its toll. As we got higher and cumulatively more fatigued, the simplest of tasks were getting harder and harder. Putting my boots on in the morning took up to 15 minutes while duties such as collecting snow for melting or digging out the camp would leave me desperately short of breath.

The fixed lines

The next day, our guide, Kevin, returned from escorting our teammates back to base camp. He had spent the last three days ‘hitching’ rides on other expeditions’ rope teams to catch us up. It was great to have Kevin back – not only did he bring positive energy to the team but it meant that we now had a two-to-one client-guide ratio in the team. However, our high spirits were dampened somewhat during our evening meal when sombre news came in over the radio. A climber had died from a fall on the Denali Pass Traverse, also known as the Autobahn, a steep snow and ice slope above High Camp. It was a timely reminder of how dangerous the mountain is and of the challenges that lay ahead of us.

We also received a daily weather forecast which suggested the conditions would be much improved the following day so we mentally prepared to tackle the formidable Headwall where a series of fixed lines would be used to get us up the steepest and most exposed part of the West Buttress.

From Camp 3, we stopped using the sledges and switched to our backpacks for carrying loads. The terrain was simply too steep to haul sledges. It also required that we switch from snowshoes to crampons for the same reason. Personally, I much preferred this – I’ve plenty of experience carrying heavy loads on mountains and always found the sledges much more challenging.

We left camp on the north side and followed tracks leading up the huge snowy face of the Headwall. It was busy on the route as a backlog of climbing teams had built up at Camp 3 due to the bad weather. At around 4,650m, we hit the bergshrund, a mighty crevasse separating the shifting glacier from the mountain, marking the start of the fixed lines. There are two fixed lines, put up and maintained by the park rangers and miscellaneous guides. One line is for ascending and the other for descending.

We used our ascenders (AKA jumars) to move up the 50-degree slope, making sure not to step on the ropes. Despite the gradient, our heavy packs and the queues, we made reasonable time and after around an hour and a half of shuffling up the line, we arrived at the col in the West Buttress at around 4,900m. From there, we moved along a rambling ridge to a series of rambling snowfields just below the enormous rock of Washburn’s Thumb. We cached our gear for the final time below High Camp at one of these fields before returning to Camp 3.

As we began our descent, our guides were approached by another expedition team who had two climbers who needed assistance descending. The team were moving to High Camp but two of their members were suffering from altitude sickness and needed to descend immediately. We took both climbers, one on each rope team, and began to head onto the fixed lines.

Almost immediately, our teams ran into trouble. Both climbers were struggling and repeatedly fell during the descent on the fixed lines and struggled to find the strength to get themselves back up and continue down. In such a situation, there is very little anyone can do to help as we’re all spread out along the rope teams and are focused on our descent. Our guides offered advice and encouragement but, essentially, it came down to the climbers to get themselves down the ropes.

It meant that our descent was delayed significantly as time and again we had to stop while our new team members struggled on. Throughout, I was unable to change my gloves as my warmer pair were in my backpack which I couldn’t access. Finally, we reached the base of the fixed lines and managed to pick up the pace as we descended the snowy face of the headwall and marched back into Camp 3 after an extremely long day.

That night in my tent, I noticed that the tips of my fingers were discoloured – a sign of frostnip and early frostbite – caused by the extended period I spent exposed on the fixed lines. Concerned that it may stop me from summiting, I kept the condition to myself and made sure to keep my hands as warm as possible by sleeping in my mitts and making sure I always had thicker gloves to hand while climbing.

We took one more rest day at Camp 3 which we used to go on a short acclimatisation hike to a dramatic rocky escarpment called The Edge of the World at the end of the plateau which has superb views of Mt Foraker, the Kahiltna Glacier and the West Rib. The next day, we left our tents in place as there were tents cached at High Camp from previous expeditions, and left Camp 3 for the fixed lines again.

This time, there were far fewer people on the route so we made much quicker time on the ascent to the col. From there, we continued past our cache and Washburn’s Thumb and picked our way along the thrilling and exposed ridge to the plateau where High Camp (Camp 4) is located. Even though the ridge is only one kilometre long, it takes a long time as there are several fixed rope sections as well as steep, exposed scrambles that have to be manoeuvred over.

Finally, we rolled into camp and set about pitching and setting up camp. High Camp is a far more hostile, exposed and colder campsite so less effort is put into home comforts. No mess tent is put up, vestibules weren’t dug and the toilet is a more basic affair. On the plus side, it is also the most picturesque camp with the humongous Autobahn leading up to Denali Pass towering above.

The following day – our 15th on the mountain – was used to acclimatise to the new altitude and test our gear for the upcoming summit attempt. This meant checking all our warm-weather gear and making sure we had everything we needed for the coldest day of the ascent. Two of our guides also returned to our cache to retrieve the supplies we’d left there.

Summit day

Summit days usually mean a frightfully early start – often in the middle of the night – to make use of the daylight and best conditions. However, the one advantage of climbing on a mountain as far north as Denali is that it never gets dark at that time of year so our summit day wasn’t dictated by the daylight. As such, we got up at the civilised time of 8am and set off for the Autobahn at around 11am.

Conditions were ideal. It was cold, of course, but it was sunny and crucially, not too windy. The traverse across the Autobahn to Denali Pass is arguably the most dangerous section on the mountain. Just days earlier, there had been a fatal fall. The traverse has been secured somewhat with a series of pickets and lines but still feels exposed.

It took a full two hours to make it to Denali Pass at 5,545m where we could take our first rest of the day, eat some food and drink some water. From here, we continued upwards picking our way through a series of rocky plateaus and snowfields. It was here that I began to struggle. To avoid frostbite, we were all trying not to leave any skin exposed on our faces. I was wearing a balaclava along with two neck gaiters but was struggling to breathe and catch my breath.

As I continued to struggle, I began to stumble and flounder and doubt whether I could continue. I knew that we still had some challenging ascents ahead of us and that if I couldn’t get past this then I wouldn’t be able to summit. I kept thinking about all the money I’d ploughed into the expedition; the sacrifices I’d made to get there; everyone who knew about the climb – my colleagues, family and friends; the hope and expectation that I had built up around the seven summits; and how, ultimately, if I couldn’t summit, I would have to give up on my dream.

Eventually, when I could barely stand any longer, I turned to Kevin and told him that I didn’t think I could continue.

Fortunately, he wasn’t going to give up on me that easily and took the time to pause and talk me through the issues. I loosened my balaclava, exposing my lips and nose, but immediately found breathing easier. Kevin explained that I just needed to regulate my breathing with my footsteps and stay calm. Focus on putting one foot in front of the other; pause before I push off with my front foot; take smaller steps; and breathe in and out with each step.

It worked. I immediately felt stronger, found my rhythm and sensed my confidence returning. Soon enough, we arrived at a much larger plateau, aptly named the Football Field, just before the final significant climb of the mountain, a slope called Pig Hill. I’ve never come so close to giving up on a climb before and I couldn’t thank Kevin enough. It was a relatively simple problem with an obvious solution but in my exhausted state, I needed a calm voice to talk me through the issue.

Despite its steepness, Pig Hill is not a long ascent. A series of switchbacks help to take the sting out of the ascent to the ridge called the Horn at 6,100m. From here, there was only one section left: the summit ridge which runs around 400m along a series of cornices and overhangs to a final giant cornice, and the summit of North America at 6,190m.

It was a thrilling end to a punishing climb, one that tested me more than I ever imagined possible. The summit was just wide enough for the six clients to stand on while the guides stepped aside and watched on as six grown men burst into tears and hugged each other. The gravity of what I had achieved finally began to sink in. I had trained for over a year for this moment, sunk thousands of pounds into the expedition and joked with my friends that my life had basically been segmented into two epochs: BD (Before Denali) and AD (After Denali). Finally, BD was over and I could move on and actually enjoy the thrill that comes with topping out on a mighty mountain.

The view, of course, was sensational. A sea of clouds stretched as far as I could see, pierced only by enormous snowcapped peaks.

Apparently, there is a US Geological Survey summit marker on Denali but it was buried under snow when we were there. We posed for a handful of photos but it was a hurried affair. It was around -20°C so any exposed skin – such as those working smartphones – is extremely vulnerable. Soon enough, it was time to dry our tears, put our cameras away and begin the descent.

The descent

It is often said that reaching the summit is only half the story – over 75% of all falls occur during the descent. With this in mind, we doubled down and concentrated as we picked our way back along the summit ridge and down Pig Hill. As we arrived at the Football Field, we came across two climbers who had been stranded at around 5,970m for at least a day. We paused to help how we could by digging a snow cave while our guides worked with another guide on the mountain to arrange a rescue before we continued our descent.

Later, we spotted a rescue helicopter overhead but, unfortunately, due to high winds, it was unable to get the climbers off the mountain that night. Sadly, by the time the helicopter could return, one of the climbers had died while the other was suffering from severe frostbite and hypothermia.

By the time we made it back to camp, it was nearly midnight and we had been out for over 12.5 hours. We dived into our tents, scoffed rehydrated meals and drank as much water as possible before doing the only thing we could manage: sleep. I had taken care to keep my hands covered all day and was relieved to find that my frostnip hadn’t deteriorated especially considering a member of our group had developed some as well during the summit day. That said, I had damaged the skin on my fingers which would take several weeks to eventually heal.

We slept late the next morning before packing up our camp and descending the fixed lines – this time trouble-free – to Camp 3 where our tents were still in place for us. Our final day was intense as we descended to base camp in one day, stopping at Camp 2 and Camp 1 to collect any cached supplies we had left.

Heavy snowfall had covered many of the crevasses below Camp 3 which meant the crevasses were almost impossible to spot. As I was leading the first rope team, I was the sacrificial lamb so to speak! It wasn’t long until I went neck-deep into a crevasse. It happened so quickly, I didn’t really have time to be scared but it was an alarming feeling having the ground beneath you disappear.

Fortunately, I had completed a day of crevasse rescue training in Scotland earlier in the year which put me in good stead. I was able to arrest my fall and avoid any injuries or sliding any further into the abyss. It was then a matter of using my ice axe to scramble out of the crevasse. As the lead climber on my rope team, it wasn’t the last time I went into a crevasse that day – I stopped counting after the sixth time!

The day – in fact, the expedition – culminated in the ascent of Heartbreak Hill which lived up to its name. It was our final challenge of the expedition but we were rewarded with a case of ice-cold beers which had been left in place at base camp for us to celebrate with. The next morning, we caught the first planes off the glacier and, in a flash, we were back in civilisation and ordering flat whites, taking hot showers and sleeping on soft beds.

It had been one hell of a climb. Nineteen days surviving and climbing on a glacier had been as hard as I had feared but even more rewarding than I had hoped. Whether or not I climb any more of the seven summits is almost irrelevant. I will always have Denali, my tall one.

Climbing Denali: the essentials

What: Climbing Denali, the highest mountain in North America and my fourth seven summit.

Where: The itinerary includes two nights before the expedition in Hyatt House (or similar) in Anchorage along with up to 21 nights camping on the mountain. While climbing all nights are in three-man tents. When you come off the mountain, you will have to pay for at least one night in Talkeetna (at Swiss Alaska Inn or similar) and any remaining nights in Anchorage (at least one night).

When: The climbing season on Denali starts in late April and continues through the middle of July. Although it’s colder earlier in the season, May and June are considered the best times to climb as they can still offer milder temperatures with fewer crevasses. By late July, the lower glacier is more dangerous due to melting snow bridges over crevasses while planes may not be able to land at base camp.

How: I joined the American Alpine Institute (AAI) on a guided climb via the West Buttress. As I am based in the UK, I booked via Jagged Globe who organised international flights and advised on gear and other logistics. However, in hindsight, I would recommend booking directly with AAI and cutting out the middleman.

Prices from AAI start at $11,995 USD and include all accommodation, breakfast and dinners on the climb, three guides on the mountain and ground transport. You have to supply your lunches. Detailed gear lists are supplied by both AAI and Jagged Globe. Some specialist items such as snowshoes, sleeping bags and down jackets are available to rent from AAI.

To enter the USA, most nationalities will need to apply for an ESTA at least 72 hours before travel. The fee is currently $21 USD.

I flew to Alaska with British Airways and Alaska Airlines via Seattle (outbound) and Portland (inbound). Book flights via Skyscanner for the best prices.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…