Last year, a friend of mine discovered that my parents never learned English despite moving to England in 1969.

He raised a brow in askance. “But you speak it so well,” he said, a cheeky smile tugging at the corner of his mouth as he lampooned those who had oh-so-magnanimously paid me the same compliment in the past.

He, a British-born Asian like me, knew there was no reason for me not to speak English well. After all, I was born, raised and educated in England.

Perhaps I shouldn’t be snarky about the compliment. After all, English is my second language despite the fact that I write, think and dream in it (and only it).

My first language or ‘mother tongue’ is Bengali and though it has been consigned to conversations with my mother, I am thankful that I have it. It borrows from English certainly, but its unique colloquialisms and turns of phrase bring a richness to my life that would otherwise be absent.

As a writer (and indeed a reader), I often make note of particularly lovely sentences.

[It’s] the kind of laughter that has no lungs behind it. It sounds rather like the rustling of fallen leaves.

You can hear this laugh, no?

Dementia wanders through the corridors of their minds, switching off lights. And the darkness left behind often crepitates with phantom terrors.

Crepitate. What a word!

I don’t read in Bengali but my mother will occasionally say something wonderfully humbling or amusing in a way that can’t be translated to English.

Amar shoril ekere kulya zargi

The literal translation to this is ‘my body is opening away’, the best translation is ‘my body is loosening at the seams’, but neither captures the poignancy of a woman mourning the loss of her health.

In an entirely different mood, my mother once remarked:

Tai ekshor fon gontor farborni

This wonderfully caustic insult was flung at a particularly dim neighbour. The phrase – “as if she could count a hundred pounds” – isn’t nearly as stinging in English. The nuance and bite is entirely lost in translation.

Occasions like the above remind me how lucky I am to speak two languages, how fortunate to be able to access, on whim, the words of another country on another continent and use them to turn a charming phrase or carve a cutting insult.

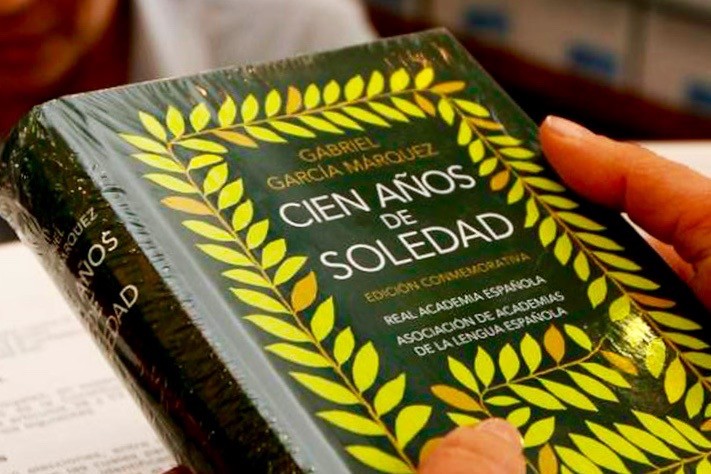

These occasions also make me lament the lines I’ll never read. What great a pleasure it must be to read Gabriel Garcia Marquez in his own language. I tried to do it once but gave up when I realised my Spanish wasn’t nearly good enough. I’m still practising, but I worry I’ll never reach a point where I can enjoy the subtleties of the language, or the untranslatable gems that bring me such joy in Bengali.

If it were possible to urge monolinguals, without condescension, to learn a second language, I would do it. I’ve benefited from one of the best state educations in the world, but I do believe it fails us when it comes to language.

One only has to travel to Norway or Switzerland to see how a second language can be learned seamlessly alongside a first. We in the UK, US, Australia or any other English-speaking country in the world can reap great benefit from learning a second language.

Bilingualism and multilingualism open up job opportunities abroad, offer a plethora of cognitive benefits, make travel easier and even strengthen the economy. They enhance perceptiveness, decision making and can even improve one’s English.

Plus, perhaps most delightfully of all, they can help you compose deliciously-worded insults for your dim-witted neighbours – and who wouldn’t want that?