In his new book, Adam Hart probes the relationships between humans and predators. Here, he explains why conservation isn’t just about animals

From big cats to army ants, Adam Hart knows about animals. Since his PhD in Zoology, he has been involved in numerous research projects across the globe, from the rainforests of Panama to the savannahs of South Africa. He is Professor of Science Communication at the University of Gloucestershire where he teaches animal behaviour, behavioural ecology, evolution, statistics, mathematical modelling, citizen science, science communication, African savannah ecology and field skills. Phew!

Adam is also a regular broadcaster on BBC Radio 4 and BBC World Service, has made more than 30 radio documentaries and co-hosted BBC documentaries Planet Ant and Hive Alive. Adam has also spearheaded some of the UK’s largest citizen science projects with the Royal Society of Biology including the Flying Ant survey, the Spider in da House app and survey, and the Starling Murmuration survey.

In his previous books, Adam examined the mismatch between human evolution and the modern world (Unfit for Purpose) and our complicated relationship with bacteria (The Life of Poo). His next book, The Deadly Balance, explores the difficult interactions between humans and predatory animals such as lions, bears and wolves, and how we can balance conservation with development to create a world where both predators and people can thrive.

Fortunately for us, Adam has found time to answer a few questions about his new book, conservation work and the travels that shaped his life.

What drew you to zoology and conservation science?

I have been interested in wildlife and the natural world for as long as I can remember. I was lucky to grow up in a “scientific” house – both my parents had scientific backgrounds – and in an area (south Devon) where the natural world was very much on my doorstep.

Rock pooling and lifting up stones and logs in woods were very much a feature of my childhood! I knew I wanted to study science from a young age, and biology and zoology in particular always had a stronger pull than the other sciences.

Conservation is an aspect of science I got into more recently, largely through my work in applied ecology and connections that were developing in southern Africa.

Your new book The Deadly Balance looks at our relationship with dangerous animals from a conservation standpoint. Why is this important?

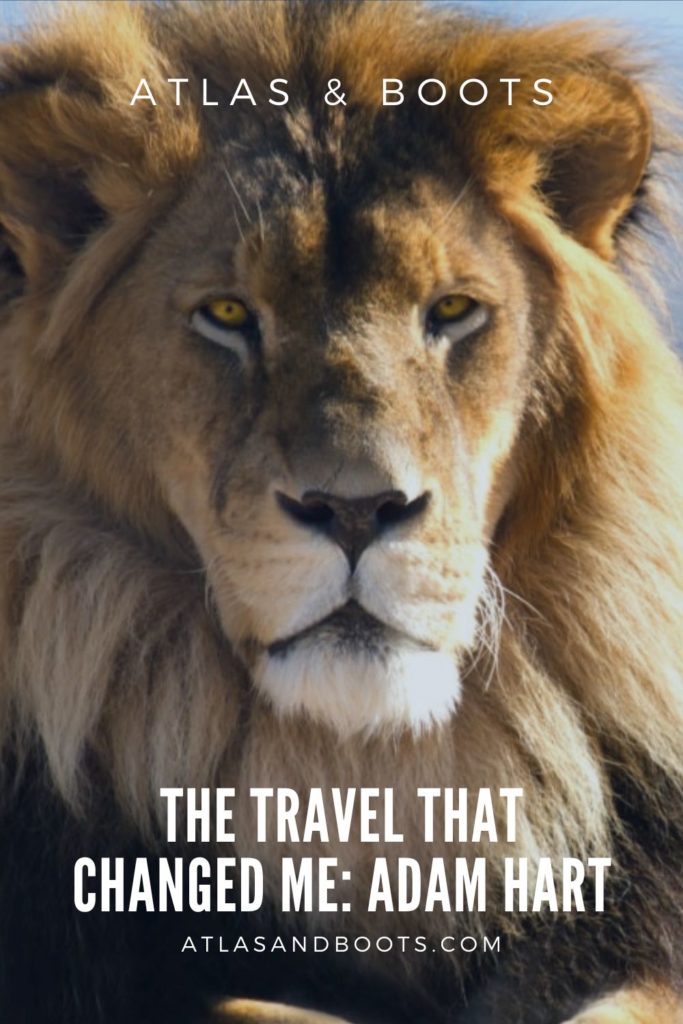

Predators occupy a very special place in the human psyche. Lions and tigers top the league when it comes to animal charisma; we have big cats as logos, wolves acting as powerful symbols of the wilderness and countless films, books and TV series centred around predators.

If you ask someone to think of an animal, there is a good chance that they are thinking of a predator. But in many parts of the world, predators and people live alongside each other, often with terrible outcomes for both. If we want a world where predators can thrive then we also have to realise that some people may end up paying the cost of having them around.

Sometimes that means losing livestock, other times it may mean physical injury or death. We can’t pretend such things don’t happen, but we can try to understand why they do and explore ways of keeping people and predators safe.

It really is a balance, and the first step to finding it is having some understanding of the sorts of problems many people face.

What is one thing you hope readers will take away from the book?

That conservation isn’t about animals. Effective conservation is about people and communities.

What are your thoughts on big game hunting? Is there a space for it in conservation?

It is a complex topic but at the moment, I think there is a space for it. Well-regulated trophy hunting can and does provide incentive for habitat and species conservation and can provide income for communities with few other options.

However, would we like that to be the case in the future? Perhaps not. The key thing is to move ahead in ways that support communities and nations doing a far better conservation job than nations like the UK. In many cases, they want to continue to use hunting as part of their conservation tool kit.

I, and many other conservation scientists, are deeply concerned about what may happen if nations like the UK try to enact legislation that is more concerned with popularity than conservation. In conservation, as in many things, it usually pays to listen more than you talk. Even if sometimes what is being said is not what you want to hear.

Ultimately, it would be good if conservation globally didn’t rely on overseas tourists, whether they carry cameras or rifles. Covid taught us how fragile that model can be.

Have you ever found yourself in a sticky situation with a predator?

I start the book by recounting an occasion when I was tracking a lion for a radio documentary with a guide in South Africa. We ended up following a lion into a network of gullies and blind corners. Once the tracks got super fresh we had the “hairs on the back of the neck moment” and beat a hasty retreat… I also once nearly stood on a crocodile in Mexico, which was a valuable lesson in looking where I’m going!

Tell us about the travel that changed you

When I was 19, I spent six months in Israel, Egypt, Cyprus and Eastern Europe, living on a shoestring out of a small rucksack. It was a fantastic time, straight out of school and before heading to university.

It made me realise that I wanted to travel a lot more and that I was pretty good at sorting things out, making do and generally getting by. Those are good lessons to learn when you’re starting out on the whole process of “adulting”.

Do you still have a dream destination you haven’t yet seen?

For me, that is Australia. And for a decent amount of time. Right now, with young children, it isn’t going to happen but I guess that is why it is called a dream destination. One day…

To guidebook or not to guidebook?

I like to make a plan and then deviate from it. I am a sucker for a guidebook but I try not to be too constrained. There is a time to wing it and a time to plan – the key is knowing the difference!

Hotel or hostel (or camping)?

Both please! I love camping and being outside. Nothing really beats it for me. I teach on a field course every year in South Africa and I always stay in the same tent. Going to sleep with the sounds of the bush and waking up with the smell of the campfire still lingering is pretty much perfect.

However, if I am going to be under a roof, then I do enjoy a good hotel and all that comes with it. High thread count sheets, room service, five-star dining, spa – bring it on!

Finally, what has been your number one travel experience?

It is hard to pick out just one moment, but I was lucky enough to spend three months studying ants in the forests of Panama and I think the first time I was alone in a tropical forest is, as a biologist, a moment I’ll always remember.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…

The predators that can hunt, kill and eat us occupy a unique place in the human psyche. In his latest book, The Deadly Balance, Adam Hart looks at our relationship with these animals from a conservation perspective.