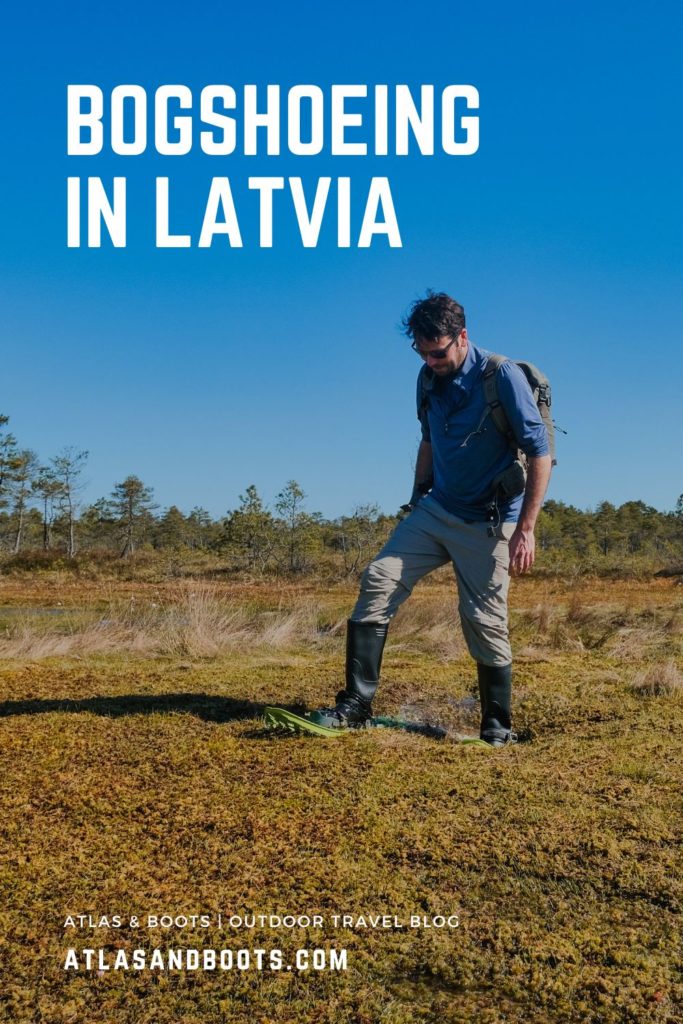

Bogshoeing in Latvia? Nope, we hadn’t heard of it either. But the wetlands of Ķemeri National Park are more than a bog-standard destination

It’s a cliché I know, but travel never ceases to surprise me. I’ve hiked all over the world – from high-altitude treks in Nepal and Pakistan to remote expeditions in Greenland and Norway – so when I was invited to the tiny Baltic nation of Latvia with its highest point just 312m (1,024ft) above sea level, I wasn’t expecting to find much in the way of expansive wilderness. But, despite its size, Latvia devotes a substantial amount of space to nature and outdoor pursuits.

My itinerary included a morning in the swamps of Ķemeri National Park located around 40km (25mi) from the capital, Riga. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, Ķemeri, known for its curative mud and spring water, was a popular spa resort attracting well-to-do travellers from as far away as Moscow. Despite its pungent smell (not too dissimilar to rotten eggs), the sulphurous water is perfectly drinkable and boasts numerous health benefits.

The well-heeled tourists of yesteryear may have somewhat dried up, but the region still attracts nature lovers looking to escape the urban sprawl of Riga. While the grand buildings of the former resort, therapeutic mud and sulphur water remain, today the region is better known for its pristine peat bogs, mossy forests and peaceful lakes.

Tourists come instead to wander the park’s trails and boardwalks or partake in outdoor activities such as rafting, stand-up paddleboarding and the rather unusual phenomenon of bogshoeing.

Now, if you’ve never heard of bogshoeing, then you’re not alone. It was entirely new to me as well.

Bogshoeing in Ķemeri Bog

The first thing that struck me when I arrived at Lielais Kemeru Tirelis (Ķemeri Bog) was the birdsong. The small car park, nestled in a thick copse of beech and pine trees, was alive with the chatter of wagtails, wood sandpipers, golden plovers and the occasional but distinctive squawks of cranes.

I was soon joined by my guide for the morning, Kristaps from Purvu Brideji (meaning ‘swamp groom’ in Latvian). A geographer and cartographer, Kristaps has been leading winter snowshoeing excursions around Ķemeri since 2015 and recently launched bogshoeing outings during the spring and summer months.

Bogshoeing is essentially snowshoeing but instead of using the lightweight large-footprint shoes for walking over snow, they’re used in much the same way for walking over the springy waterlogged terrain found in bogs, marshes and swamps (note: there is a difference).

We walked for around 10 minutes along the main track before branching off-trail into the surrounding forest. As the trees thinned and the ground became soggier, we paused to strap on our rubber boots and snowshoes.

Kristaps gave me a crash course on how to walk on bogs: take wide slow steps, don’t turn sharply or walk backwards and never cross step. He also showed me what types of terrain to avoid: the greenest, wettest grass would likely be too soggy to walk on, so try instead to aim for the more yellowish areas.

Before long, we were walking across sodden ground that would usually be off-limits to hikers, hence the absence of trails in the area. The going was fairly slow (around 2km per hour compared to 5km per hour when hiking over flat ground), but we weren’t aiming to cover lots of ground, instead trying to reach spots which would usually be out of bounds without snowshoes… I mean bogshoes!

We manoeuvred around the bog, passing picturesque pools of motionless water and stepping over the occasional tree felled by beavers, sloshing and squishing our way over the springy vegetation.

Kristaps paused occasionally to point out native plants such as edible wild berries including cranberries, crowberries, cloudberries and blueberries as well as heather and wild rosemary. The latter has hallucinogenic properties that may have been used by ancient Viking warriors to ready themselves for marauding.

The formation of bogs in Latvia began during the postglacial period, approximately 10,000 years ago as the climate became warmer and more humid. This process allowed sapropelic mud to form at the bottom of lakes, consisting of sandy soil and the remnants of plant life and animals.

The oxygen-free (anaerobic) environment of bogs, along with the presence of excessive tannins (naturally occurring chemicals used in leather tanning), excel at preserving organic materials, including bodies. A number of well-preserved bog bodies, dating from as long ago as 8000 BC, have been found in peat bogs around the world, delighting archaeologists. More recently, several World War II tanks and even a plane were discovered in Ķemeri with the bodies of their pilots and crew preserved in place.

Similarly, bog oak – oak lumber that has been buried in a peat bog for hundreds or even thousands of years – is some of the world’s hardest wood. Once dried, it is said to be “comparable to some of the world’s most expensive tropical hardwoods”.

The bogshoeing itself was great fun. We stopped at a wide expanse of bog ripe for the ‘swamp shuffle’ and we took turns bouncing around a particularly rubbery patch of peat bog. Kristaps explained that just underneath the moss and grass, the water could be as deep as two meters. If it weren’t for the snowshoes, we would sink straight in up to our necks!

After a few more stops for photos and fooling around in the bog, it was time to head back to the trails. Our time had flown by. We’d covered around 3.5km over two hours and hadn’t seen another soul during our time in the bog. That’s another great thing about bogshoeing in Latvia: unless hikers have snowshoes, they can’t leave the trails and boardwalks of Ķemeri, leaving you to freely make a fool of yourself.

Bogshoeing in Latvia? It’s as silly as it sounds but outrageously good fun.

Great Ķemeri Bog Boardwalk

After finishing my bogshoeing excursion, I made the 15-minute drive to Great Ķemeri Bog, a popular spot for visitors and tourists, which offers everyone the chance to explore the bog without the need for specialist footwear.

Here, a network of boardwalks meanders among the soft vegetation, thinly spread trees and tiny dark lakes, periodically interspersed with benches and observation towers to sit and watch the, um, bog go by.

There are two circular routes to choose from: a 1.4km trail that sticks to the narrow boardwalks throughout, or a 3.4km course that takes in a number of stop-offs including an observation tower. The two-storey wooden tower provides far-reaching panoramic views across the tranquil landscape.

The Great Ķemeri Bog boardwalks are a popular destination throughout the year, particularly for photographers around sunrise and sunset, so don’t expect the same solitude found while bogshoeing. That said, I visited on a weekday in June and only bumped into a handful of people. Wherever you go, Ķemeri National Park excels at peacefulness.

Bogshoeing in Latvia: the essentials

What: Bogshoeing in Ķemeri National Park, Latvia.

When: While Latvia is a year-round hiking destination, bogshoeing can only be done when the ground isn’t frozen (otherwise it’s just snowshoeing). As such, the best time to visit Latvia for bogshoeing is between April and September. From mid-September, temperatures drop rapidly with the first snowfall as early as mid-November.

Where: I stayed at the elegant Dome Hotel right in the centre of Riga’s charming Old Town. The hotel is located down a quiet street just around the corner from Cathedral Square and the towering red-brick Riga Cathedral which can be seen from some of the rooms. Just a two-minute walk in the other direction is the grand Riga Castle, the official residence of the Latvian president.

The five-star hotel is situated in a 400-year-old building and features a spa complete with Turkish baths, massage rooms and a sauna, as well as a rooftop restaurant with gorgeous views of the cathedral.

How: I went bogshoeing in Latvia with Kristaps from Purvu Bridēji. Prices begin from €120 per person but quickly drop with more participants: €80 per person for two people; €60 per person for three or four people; €40 per person for five or six people; €25 per person for groups of nine or more. The price includes hire of bogshoes and rubber boots and transfers from Riga can be added for a small fee. Find more information here or email Kristaps at info@purvubrideji.lv.

Ķemeri National Park is about 45 minutes from Riga by car. The meeting point for the bogshoeing is located in the Lielais Kemeru Tirelis (Ķemeri Bog) car park (see map). From there, it’s a short walk before snowshoes are strapped on and the bogshoeing begins. Just a 15-minute drive around the corner is the Great Ķemeri Bog Boardwalk (see map). There is a €2 charge for parking at Great Ķemeri Bog Boardwalk.

I hired a car from Sixt at Riga Airport after flying to Riga International (RIX) from London Stansted. Several international airlines fly to Latvia. Book through skyscanner.net for the best prices.

At Stansted, I had a super early flight, so booked a night at Radisson Blu Stansted Airport, just a 2-minute walk from the terminal via a covered walkway. The hotel boasts a fantastic bar and three restaurants while the rooms are large, comfortable, stylish and most importantly of all, quiet. I left at 4am and was past security exactly 24 minutes later: perfect for a late night or early start!

I continued my journey from Latvia by train with an Interrail Global Pass. After meeting Kia in Warsaw, Poland, we went on to cover over 3,000km by rail, visiting seven countries en route to San Marino. Established in 1972, Interrail just celebrated its 50th anniversary and recently launched several initiatives including its Mobile Pass and Rail Planner app, both of which made travelling easier.

Global passes start from €503, include one month of unlimited train travel across 33 European countries and are valid for 11 months from the date of issue. Some reservation fees are charged by the national railway companies. It’s recommended to book seat reservations at least 4-6 weeks in advance. Learn more about Interrail mobile passes.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…