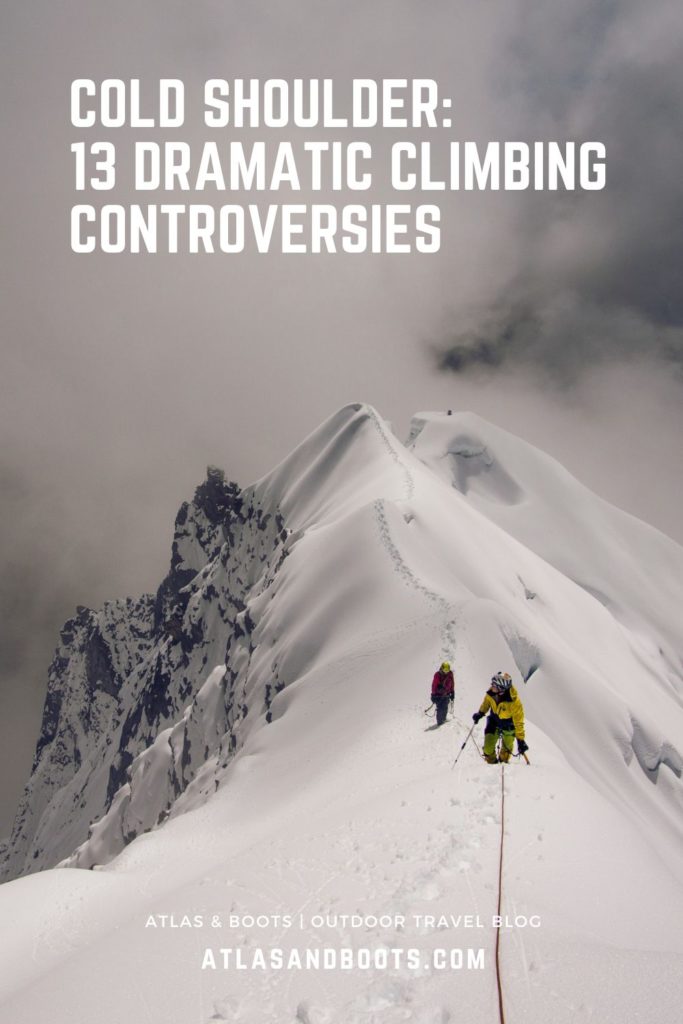

From dubious first ascents to tense clashes at high altitudes, we explore 13 dramatic climbing controversies – some resolved and others less so

There was a time when climbing controversies were sportingly confined to the slopes. The petty trivialities, the robust exchanges and the heated clashes were just part of the cut and thrust of the mountaineering world.

As the field grew more lucrative and summiteers were furnished with fame and book deals, these once-discreet disputes began to spill off the slopes.

From contested first ascents to violent clashes at high altitude, we review some of history’s most fascinating climbing controversies.

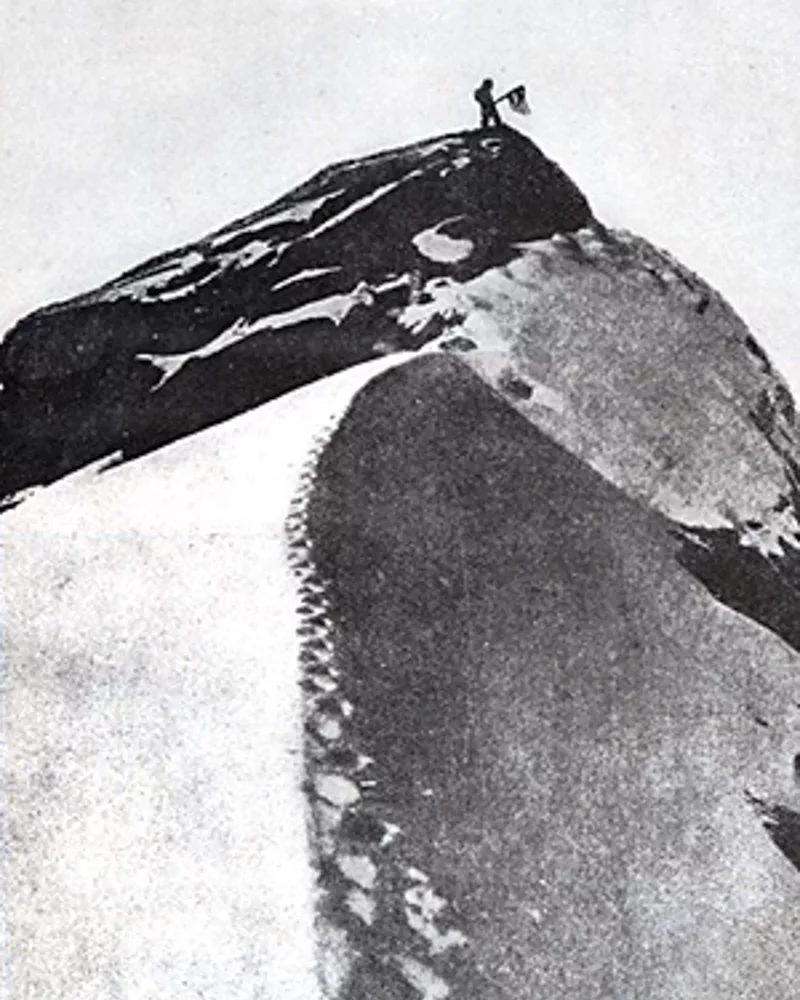

Denali: Frederick Cook, 1906

In 1906, explorer Dr Frederick Cook took a photograph that would make him famous: a flag-bearing silhouette standing atop a monochrome peak.

The figure in the picture was Cook’s climbing companion, Edward Barrill, on the summit of Denali in Alaska – or so the pair claimed.

According to Cook, he and Barrill found themselves “near the limit of human endurance” as they reached the summit of the highest peak in North America. ”At last!” he wrote in his account of the climb. “The soul-stirring task was crowned with victory. The top of the continent was under our feet.”

Members of the crew who were left on the lower mountain immediately expressed doubt. It was only in 1909, however, after Cook’s North Pole dispute with Peary, that his ascent of Denali was publicly challenged. That year, Barrill signed an affidavit stating that he and Cook had not reached the summit after all.

It is said that Barrill was bribed by Peary’s backers – he did indeed accept their money – but the map included in his affidavit correctly located ‘Fake Peak’, the stand-in for the actual summit.

In 1997, historian Robert M. Bryce found an uncropped version of the summit photo in Cook’s papers donated to Ohio State University. It showed previously hidden detail and Bryce concluded that Cook’s famous photo was actually taken on a small promontory some 4,500 metres below the summit!

Related reading: Denali’s Howl: The Deadliest Climbing Disaster on America’s Wildest Peak

Annapurna: Maurice Herzog, 1950

In 1950, a French team of climbers made history on Annapurna in Nepal. It was the first-ever summit of an eight-thousander – but tensions began before the team had even left Paris.

At the airport, expedition leader Maurice Herzog surprised his team with contracts that forbade them to write about their climb for five years, securing himself the first word on their historical ascent. His book, Annapurna, went on to sell 11 million copies.

After the five-year embargo, other members of the team published their own accounts. These apportioned less credit to Herzog and so began one of the most enduring climbing controversies.

In 1999, David Roberts, author of True Summit: What Really Happened on the Legendary Ascent of Annapurna, interviewed Herzog who remained unapologetic. He had considered letting each team member write a chapter in the book, he said, but that would have sold 1,000 copies at most.

The reason it had sold millions of copies, said Herzog, was that “Annapurna is a sort of novel. It’s a novel, but a true novel.”

Related reading: Annapurna: First Conquest of an 8000-meter Peak

K2: Walter Bonatti, 1954

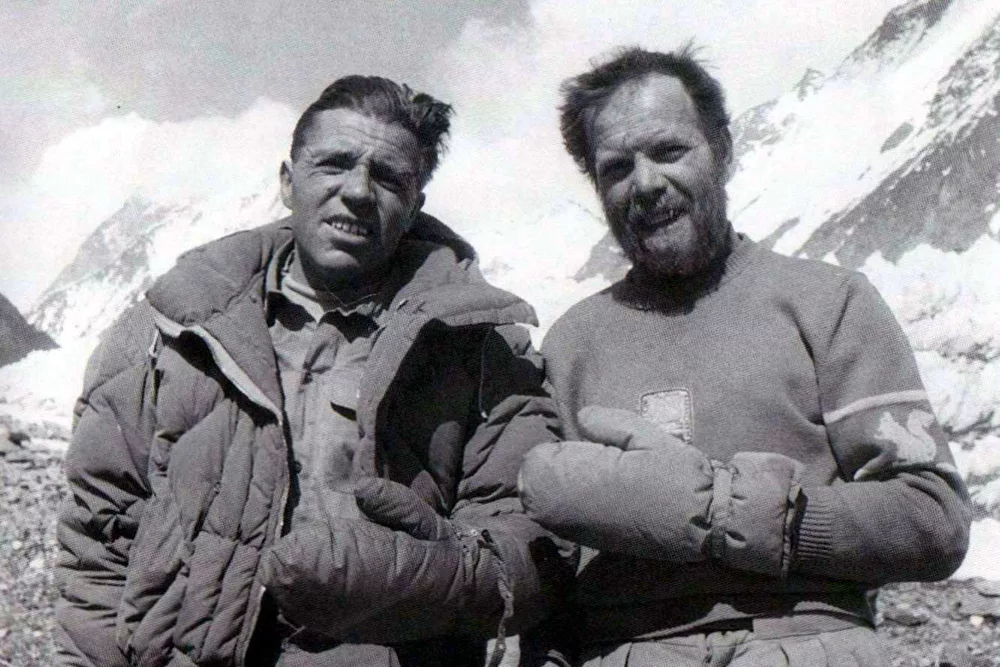

The 1954 Italian Karakoram expedition to K2 in Pakistan led to a climbing controversy that dragged on for 50 years. There is no dispute that Italian climbers Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli reached the summit of the “savage mountain”. Rather, it was how they did it that caused ill will.

Walter Bonatti, the youngest member of the team, claims that he and Hunza porter Amir Mahdi carried two 18kg oxygen sets from their seventh camp at 7,440m to around 8,100m, but were unable to reach the higher camp because Compagnoni and Lacedelli had deliberately pitched it higher than planned.

According to Bonatti, Lacedelli briefly turned on a light and shouted down to them to leave the oxygen and turn back. The light was turned off and no more was heard despite entreaties from those below. Bonatti and Mahdi were forced to spend a night in an emergency bivouac. At dawn, Mahdi raced down, but Bonatti waited until 6am before descending, still with no sign of the higher tent.

Compagnoni and Lacedelli denied this, leading to recriminations, lawsuits and defamation claims. It remains one of the most enduring climbing controversies.

Related reading: The Mountains of My Life

Cerro Torre: Cesare Maestri, 1959, 1970

With dizzying steepness, violent weather and an unclear line of ascent, Cerro Torre in Patagonia was long deemed ‘unclimbable’. Then, in 1959, Italian Alpinist Cesare Maestri claimed that he and Austrian ice climber Toni Egger had made the first ascent of the deadly spire.

Egger perished on the mountain, swept away by an ice avalanche to the glacier below. His body disappeared along with their camera. Only Maestri lived to tell the tale.

At first, the feat was hailed one of the greatest ascents of all time… and then came the doubts. Subsequent climbs and closer interrogation cast heavy doubts on Maestri’s claims. A climb of this difficulty completed in bad weather in alpine style seemed highly unlikely given the state of mountaineering in 1959.

To salvage his reputation, Maestri returned to the peak in 1970, this time with a 150kg compressor-powered bolt gun and bolted his way up the peak. This gave rise to further controversy. Mountain Magazine called Cerro Torre “a mountain desecrated” and asked, “how could a man who claimed to have climbed [it] in such impeccable style in 1959 come back and bolt his way to the top?”

Today, most experts believe that the 1959 ascent was a hoax.

Related reading: The Tower: A Chronicle of Climbing and Controversy on Cerro Torre

Nanga Parbat: Reinhold Messner, 1970

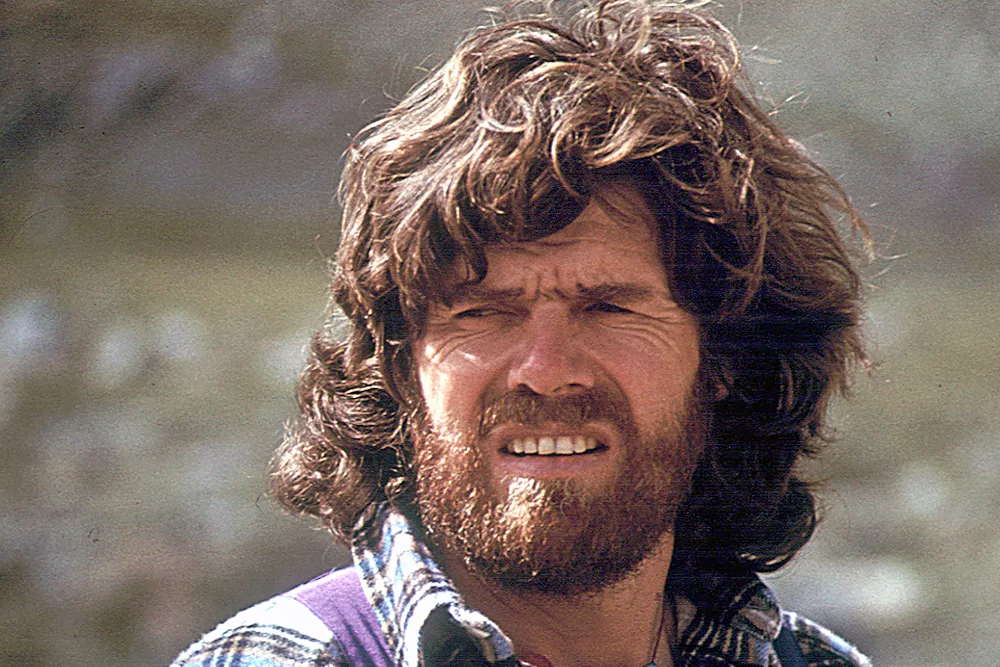

Legendary mountaineer Reinhold Messner has weathered one of history’s most egregious climbing controversies.

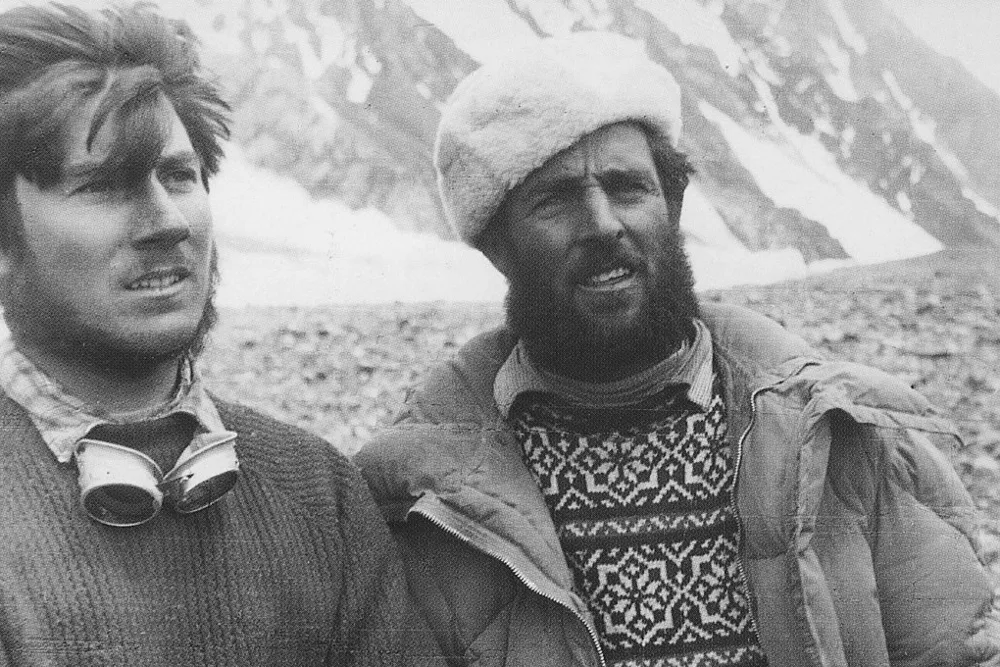

In 1970, Messner and his brother Günther embarked on an expedition to Pakistan’s Nanga Parbat, known as ‘Killer Mountain’. The brothers reached the summit via the then-unclimbed Rupal Face but were forced into a dangerous climb down the unknown Diamir Face. Messner barely survived and Günther was swept away by an avalanche.

Two other climbers, Max von Kienlin and Hans Saler, who did not reach the summit claimed that Messner sent Günther down the Rupal Face alone because he wanted to attempt the Diamir Face. “In effect,” they wrote, “Messner sacrificed his brother to his own ambition.”

Messner vigorously denied these claims and was proven right 35 years after the fateful ascent. In 2005, Günther’s remains were found at 4,400 metres on the western Diamar face and not the Rupal as claimed. Kienlin and Saler have not recanted or apologised.

Related reading: Reinhold Messner: My Life at the Limit (Legends and Lore)

Everest: Jon Krakauer, 1996

Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air is one of the bestselling mountaineering books of all time – but the events recalled within have long been contested.

Krakauer’s account of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster strongly criticised Russian climber and guide Anatoli Boukreev for descending before his clients and for declining to use supplementary oxygen.

In Boukreev’s own account of the disaster, he insists that he descended before his clients in order to prepare rescue efforts. Indeed, he undertook several solo rescues and saved three lives in the process.

Several mountaineering luminaries criticised Krakauer’s account and observed that he was sleeping in his tent while Boukreev was rescuing others.

Climber Galen Rowell said: “Boukreev foresaw problems with clients nearing camp, noted five other guides on the peak, and positioned himself to be rested and hydrated enough to respond to an emergency. His heroism was not a fluke.”

Reinhold Messner, meanwhile, defended Krakauer, saying that his description of Boukreev tallied with his own experiences and praised Into Thin Air as “a great description of reality”.

Related reading: Into Thin Air and The Climb

Kanchenjunga: Oh Eun-sun, 2009

In April 2010, after a successful summit of Annapurna, South Korean mountaineer Oh Eun-sun made history as the first woman to climb all 14 eight-thousanders – but her feat was almost immediately called into doubt.

Her nearest rival, Spanish climber Edurne Pasaban, questioned Oh’s 2009 summit of Kangchenjunga. Pasaban claimed that two of the three sherpas that climbed with Oh confirmed that she had failed to reach the summit. Oh’s only evidence was a blurry photo, calling her account into further doubt.

Elizabeth Hawley, founder of The Himalayan Database, spoke to both climbers and marked Oh’s summit as ‘disputed’. In contrast, Reinhold Messner, the first person to climb all 14 eight-thousanders acknowledged Oh’s achievement after meeting with her.

In August 2010, the Korean Alpine Federation judged that Oh “probably failed” to reach the summit, concluding that her photos did not “seem to match the actual landscape” and that “Oh’s previous explanations on the process of her ascent to Kangchenjunga are unreliable”.

Related reading: The Last Great Mountain: The First Ascent of Kangchenjunga

Cerro Torre: HAYDEN KENNEDY and Jason Kruk, 2012

In 2012, North Americans Jason Kruk and Hayden Kennedy climbed Cerro Torre using Cesare Maestri’s ‘Compressor Route’. On their descent, they removed 125 of Maestri’s myriad bolts, believing that they were helping to restore “a mountain desecrated”.

When they arrived in El Chalten, however, they were arrested by local police. While purists agree that Maestri should not have placed so many bolts in the mountain, the removal sparked a heated debate.

Some say that Kennedy and Kruk effectively demolished the Compressor Route, blocking lesser climbers from the peak – a decision they should not have taken unilaterally. Others argue that it was an altruistic act, pointing out that no one has a ‘right’ to climb this savagely steep peak.

Leo Dickinson, one of the first journalists to accuse Maestri of fraud, said: “Perhaps the saddest piece of Maestri’s legacy is denying his fellow Italians their rightful place in history. Now that this ridiculous via ferrata has been removed, an ascent of Cerro Torre will have meaning once more. It will take its rightful place as one of the world’s most inaccessible summits. Please let no one put back the bolts.”

Related reading: The Tower: A Chronicle of Climbing and Controversy on Cerro Torre

Everest: Ueli Steck, Simone Moro, Jon Griffith, 2013

It was a clash that shook the mountaineering world: three European climbers “threatened by an angry mob of Sherpas” after a disagreement 7,000 metres up Everest.

Sherpas had long been portrayed in the media as the tireless, ever-smiling companions of western climbers – but here was a different story.

The conflict started when a team of Sherpas accused three elite climbers – Ueli Steck, Simone Moro and Jon Griffith – of dislodging a block of ice that struck one of the Sherpas. The trio denied the accusation and the exchange grew heated.

When the three men later returned to Camp 2, a large group of Sherpas attacked them, punching, kicking and throwing rocks. Moro said they were told that “by that night one of them would be dead and the other two they would see to later”.

The 2015 documentary film Sherpa shows some of the heart-stopping conflict. Tensions grew particularly high after Moro insulted a Sherpa using a Nepalese slur.

Thankfully, other climbers intervened, including Melissa Arnot whom Steck credits with saving his life. The situation calmed after an hour and the trio fled back to base camp.

Related reading: Ueli Steck: My Life in Climbing (Legends and Lore)

Project Possible: Nims Purja, 2019

When Nirmal ‘Nims’ Purja set out to climb all 14 eight-thousanders in the space of seven months, mountaineering luminaries said it was impossible. In a respectful nod to the naysayers, Purja named his plan ‘Project Possible’.

Needless to say, Purja did indeed complete the feat – in just over six months, breaking the previous record by an incredible seven years and three months. Along the way, he broke a slew of other records and even saved four lives. The achievement should have been universally lauded, but sadly it was not so.

Legendary mountaineer Sir Chris Bonington said: “What he has done is quite extraordinary, but it isn’t mountaineering. Real mountaineering is exploratory – finding new routes up to big peaks … I don’t see this as a major event.”

Stephen Venables, the first Briton to climb Everest without oxygen, said: “The fact that he used supplementary oxygen detracts from the feat. I know he also used fixed ropes. It isn’t exactly alpinism as I understand it. He is of course supremely fit and determined but I find it hard to get enthused by what he’s done … In the history of mountaineering it will only be a footnote.”

As a counterpoint, Reinhold Messner defended Purja, suggesting that purists should try to repeat Purja’s feat without the use of supplemental oxygen.

The criticism did little to discourage Purja. In January, he completed the first winter ascent of K2, proving that he truly is one of the best mountaineers in history.

Related reading: Beyond Possible: One Soldier, Fourteen Peaks ― My Life In The Death Zone

Eight-thousanders: Kristin Harila, 2023

Four years after Purja completed Project Possible, Norwegian climber Kristin Harila – a former professional skier – claimed to have achieved the same feat in just three months and one day; three months and five days faster than Purja’s breathtaking record.

Harila’s achievements have not been without controversy. Prominent sherpa Mingma G criticized her ascent of Manaslu, the world’s eighth-highest mountain at 8,163m, due to her team’s apparent heavy reliance on helicopters to stock camps before the successful climb.

In a 2023 interview with ExplorersWeb, Mingma G criticised Harila’s tactics and suggested that her team was using helicopters to shuttle sherpas to higher camps – opening the route from above rather than working their way up the mountain.

“This video is from yesterday. The helicopter is dropping rope, oxygen and sherpas to Camp 2 on Manaslu. [Sherpas] will open the route from Camp 2 to Camp 1,” Mingma G told the website.

“A new model of climbing is developing in Nepal. It was exactly [the same] on Annapurna too. [Sherpas] dropped at Camp 3 and opened downward. I was surprised to read the news of [Harila’s team] climbing from base camp to Camp 3 in one push on Annapurna. I know the snow and route. [Harila’s team] had three shuttles to Camp 2 and one to Camp 1 yesterday. This will ruin the image of the Himalaya and the prestige of the sherpa.”

The rising reliance on helicopters in the Himalayas to transport people and supplies has been criticised for its environmental impacts and for reducing employment opportunities for local mountain communities. In response, during the 2023 spring season, the local government in the Khumbu region surrounding Everest temporarily limited air service on Everest base camp to promote traditional transportation methods using porters and yaks.

Related reading: Honouring High Places: The Mountain Life of Junko Tabei

Shishapangma: Anna Gutu & Gina Rzucidlo, 2023

In 2023, two American women and two Sherpa guides died in avalanches on Shishapangma, an 8,027m peak in Tibet, China. Shishapangma is the 14th-highest mountain in the world and the lowest of the eight-thousanders. The climbers were racing to become the first American woman to scale all 14 of the world’s 8,000m peaks.

Anna Gutu was guided by Mingmar Sherpa while Gina Rzucidlo was led by Tenjen ‘Lama’ Sherpa. Both Mingmar and Tenjen died roped to their clients on Shishapangma. The tragic incidents raised several questions about the ethics of chasing such records.

Anna Gutu was a relative newcomer to mountaineering but quickly ticked off summits on the world’s highest mountains after she was inspired to climb by Purja’s 2021 film, 14 Peaks: Nothing Is Impossible.

Gina Rzucidlo had been climbing from a young age and had completed several high-altitude treks and climbs – including the seven summits – before she decided to attempt all 14 eight-thousanders around 2021. Both women had climbed 13 of the 14 peaks in quick succession, converging upon the same final mountain on the same day.

Interest in climbing 8,000m peaks has increased over the last decade, as the proliferation of fixed ropes and bottled oxygen has made the mountains easier to climb. Likewise, the use of helicopters can cut days – or even weeks – off lengthy approach treks.

This allows some clients to be shuttled between base camps, using the acclimatisation from one peak to climb another. A climber could potentially tick off several peaks in a year on expeditions that lasted just a couple of weeks as opposed to months.

Both climbers were able to draw on their considerable means in their attempts to achieve the record. Neither Gutu nor Rzucidlo were sponsored athletes and both privately funded their climbs which costs hundreds of thousands of dollars in total.

There was also some animosity between the two with Rzucidlo once referring to Gutu as “just a typical Instagram climber”. Both women were planning to document their feats: Rzucidlo intended to write a book while Gutu had a cameraman filming her climbs.

Once Rzucidlo learned that Gutu was closing in on the record, she contacted Seven Summit Treks and requested the help of Tenjen ‘Lama’ Sherpa. Tenjen, however, was already on another climb with another client, and the amount paid by Rzucidlo to send their star Sherpa at the last minute was significant. According to Seven Summits manager Dawa Yangzum, Rzucidlo paid the company a $30,000 deposit, and Tenjen arrived in China the following evening to guide her on Shishapangma.

The tragedy highlighted how the rush to break records on the world’s highest peaks is driving climbers – and their guides – onto dangerous mountains in higher numbers.

Related reading: Everest, Inc: The Renegades and Rogues Who Built an Industry at the Top of the World

Harassment and assault: Nims Purja, 2024

In 2024, the New York Times published accounts from two women who independently alleged that Purja sexually harassed and assaulted them. In one account, Finnish climber Lotta Hinsta said that in 2023 Purja invited her into his Kathmandu hotel room under the pretence of a business meeting. Here, it’s alleged that he undressed her against her consent and started “masturbating next to her”.

In another account, California physician April Leonardo accused Purja of making unwanted physical and verbal advances towards her during a 2022 expedition to climb K2 – the world’s second-highest peak – in Pakistan.

Purja’s public relations team denied the claims via a lengthy statement published on Instagram Stories following the article’s release.

“A story has been published making heinous allegations to which Nims unequivocally denies any wrongdoing,” the statement read. The statement denied any allegations of sexual abuse or harassment and said the NYT story “was biased and had a pre-determined narrative and outcome” and that the “allegations are defamatory and false”.

In the days following the publication, several mountaineers, brands and even Nepali politicians praised the women featured in the NYT piece and called for action against Purja and his Elite Exped guiding company which takes clients to Everest and other high peaks around the world.

Furthermore, backpack manufacturer Osprey has cut ties with Purja and stated that he is no longer an Osprey ambassador. Red Bull and Scarpa are continuing their partnerships with the mountaineer.

Related reading: In Her Nature: How Women Break Boundaries in the Great Outdoors

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…