The Fram Museum in Oslo strikes the perfect balance between fact and fantasy, appealing to exploration junkies, history buffs and culture seekers alike.

Norwegians have a rich and successful history in polar exploration. Here in the UK we revere the names of Shackleton and Scott while only whispering those of Nansen and Amundsen. The legends of Shackleton and Scott are lauded for against-the-odds survival and ultimate sacrifice, while their Norwegian counterparts are known for triumphing in relatively undramatic glory.

It has been argued that where Shackleton and Scott failed in their quests, Nansen and Amundsen excelled due to diligent preparation, attention to detail and the skills only ingrained in those that are bred in the polar regions – those from countries like Norway.

Atlas & BOots

The Fram Museum in Oslo doesn’t wax lyrical about this classic era of polar exploration, nor is it an exercise in jingoism showcasing Norwegian superiority in the field. The museum of course illustrates the adventure, danger, privation and bravery of these pioneers, but it also celebrates the men behind the explorers and reviews the equipment carried, the scientific and medical research completed and the animals that accompanied the expeditions.

The museum is literally built around the two ships that define Norwegian polar exploration: the Fram and the Gjøa. Housed in two tall buildings designed to accommodate the vessels, the museum comprises numerous exhibitions and offers an opportunity to board and explore the legendary Fram.

Below, we take a look at some of the key journeys of discovery at the core of the Fram Museum in Oslo. If you’re ever in Norway’s capital, it’s not to be missed.

First crossing of Greenland (1888-1889)

Fridtjof Nansen is a legend in Norway: hero, pioneer, statesman and humanitarian. His name first entered the annals of history when together with five companions, he became the first to cross the interior of Greenland.

Nansen rejected the complex colonial-style organisation and heavy manpower that had beset previous Arctic ventures, and instead planned his expedition for a small team of six.

After six weeks skiing across the icecap from east to west, the team arrived triumphantly at Godthaab (Nuuk) on the west coast of Greenland.

There they spent the winter, where Nansen paid great attention to the details of hunting, fishing and the lives of the local inhabitants – honing skills that would prove intrinsic in future polar expeditions. In 1889 they returned to Norway as national heroes.

Nansen’s Arctic expedition (1893-1896)

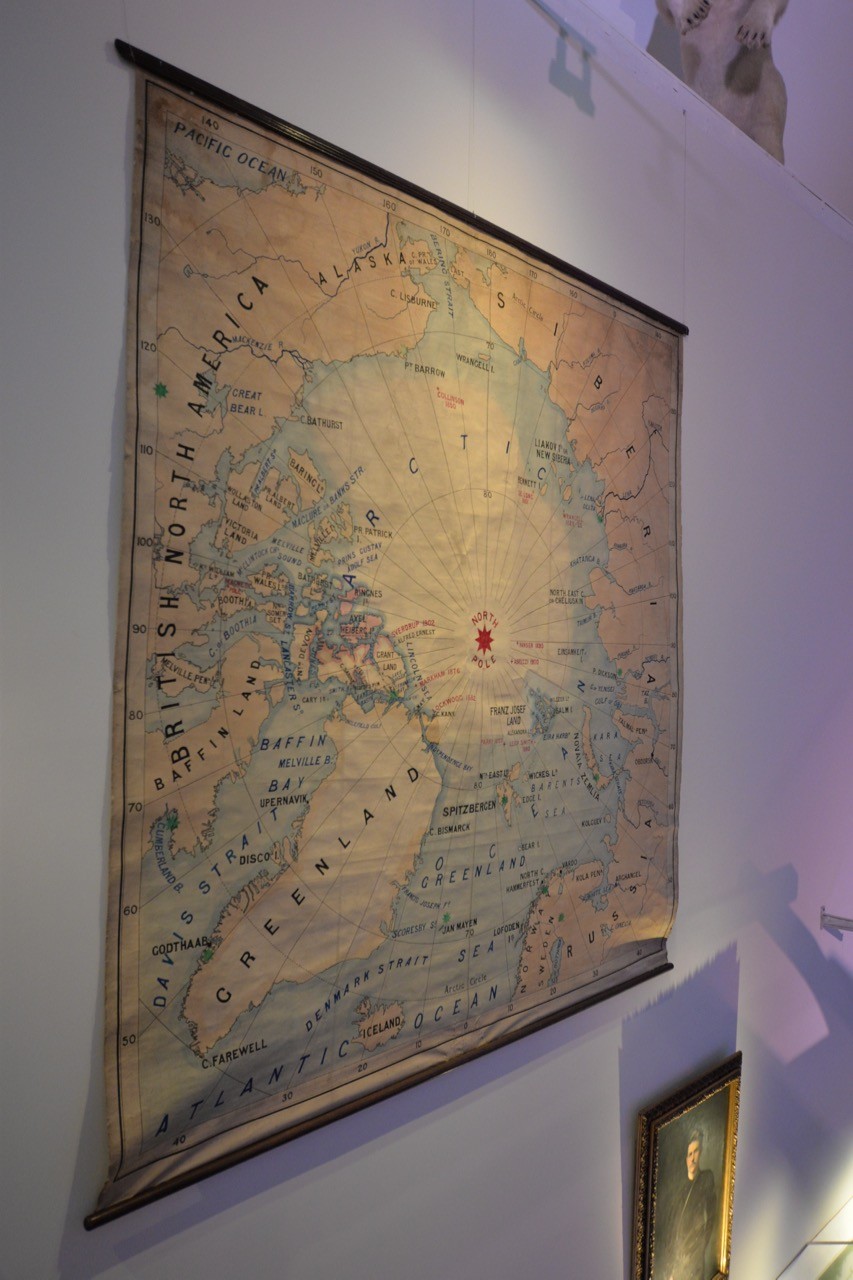

Nansen returned to the Arctic intent on discovering if it were possible to reach the North Pole by using the natural drift of the polar ice. The plan was to sail a ship as far north as possible until it became entombed in pack ice that would hopefully drift across – or as near as possible to – the North Pole.

Enter the Fram: a ship of extraordinary strength designed to endure the crushing pressures of the Arctic pack ice. The ship, which in English means ‘forward’, was built from the toughest oak timbers available, used an intricate system of crossbeams and braces throughout, and featured a rounded hull designed so that it would slip upwards out of the grip of packing ice.

The expedition was largely a success. Although the Pole was not made, Nansen proved that his theory was correct. The ship reached as far north as 84°4’N and Nansen made an overland “dash for the pole” reaching 86°13.6’N – almost three degrees beyond the previous Farthest North mark.

Northwest Passage (1903-1906)

Roald Amundsen’s expedition on the Gjøa, also housed at the Fram Museum, was the first to conquer the Northwest Passage solely by ship. With a crew of six, Amundsen traversed the passage in a three-year journey.

After two winters spent in the Canadian Arctic, Amundsen finally cleared the passage. He then skied 800km (500mi) to the city of Eagle in Alaska. There, he sent a telegram announcing his success before skiing the return journey to rejoin his companions.

Amundsen’s South Pole expedition (1910-1914)

Roald Amundsen was granted the use of the Fram for a new expedition to the Arctic. However, Amundsen had kept secret his real intentions and so when he set sail, to the surprise of the watching media and his beneficiaries, he sailed south towards the Antarctic instead of North towards the Arctic.

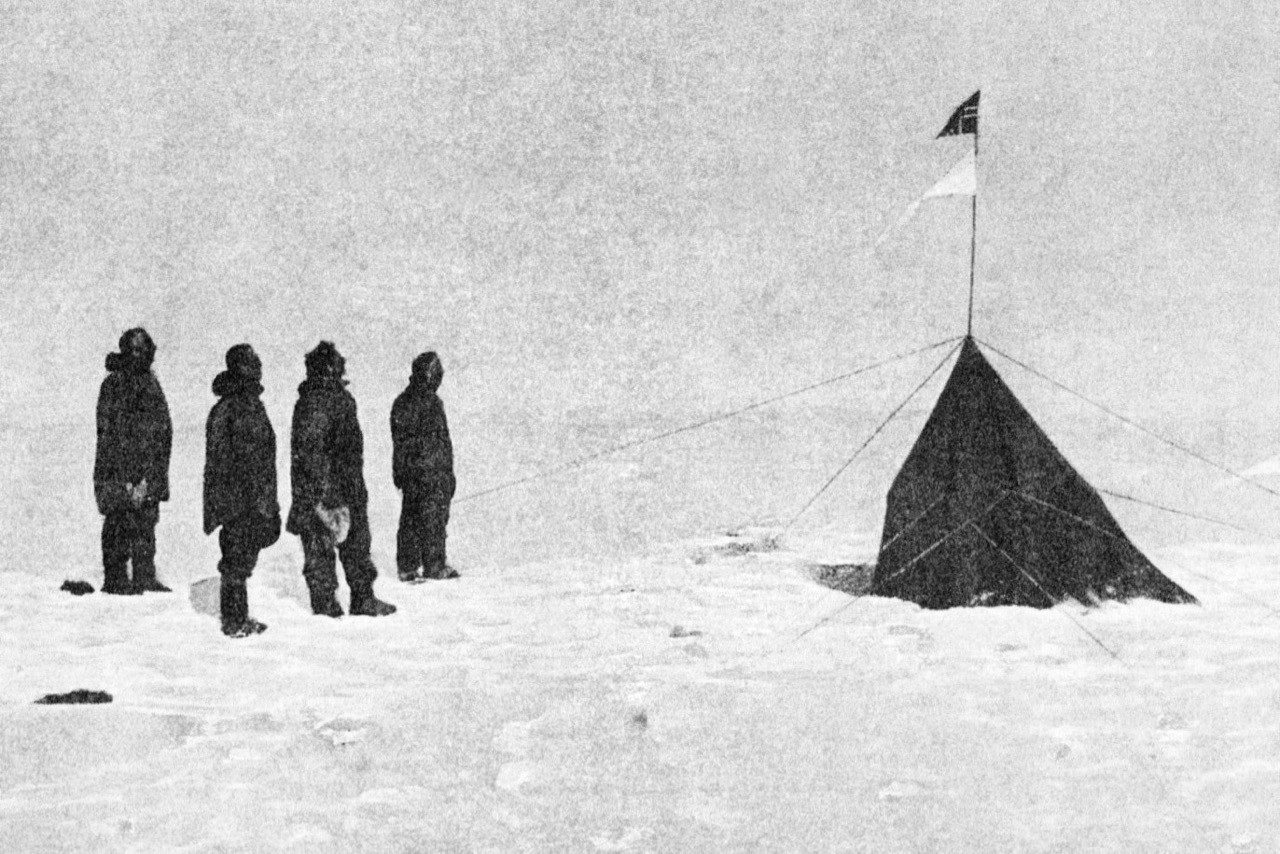

The South Pole expedition of 1910-12 was completed successfully. Amundsen and four companions reached the South Pole on 14th December 1911, a month before Robert Falcon Scott’s group arrived.

Amundsen had used the skills learnt on the Gjøa expedition to the Northwest Passage: dog driving, igloo building, clothing and polar survival from the Inuit. Amundsen reached the South Pole with his four companions and 17 sled dogs. They spent three days in the area, taking measurements and circling the Pole on skiing trips to ensure that they had indeed covered the invisible South Pole. They then returned to meet the land party after a total absence of 99 days and a distance of 3,000km (1,800mi) travelled with loss of no men.

The N24/N25 flight towards the North Pole (1925)

This time, Amundsen took to the skies attempting to fly to the North Pole with five crew members in two aircraft: the N24 and the N25. They started from Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, and flew in formation to 87°43′ N, where they landed on leads in the drift ice after more than eight hours of flying time.

The N24 had been damaged on take-off and could not be flown again so the six men struggled for three and a half weeks to create a take-off strip on the drift ice. Using primitive tools and surviving on very limited food rations they finally managed to get the remaining N25 airborne with all six men on board. Eight hours later and out of fuel they landed safely off the north coast of Nordaustlandet, Svalbard. A small ship which was by chance in the area returned them to Ny-Ålesund.

The Norge flight (1926)

Amundsen again took to the skies with fellow explorers Lincoln Ellsworth and Umberto Nobile. The men flew with 13 other crew members in the airship, Norge, from Ny-Ålesund in Svalbard over the North Pole to Teller in Alaska, USA. This was the first undisputed sighting of the North Pole. Additionally, it was also the first expedition to have crossed the Arctic Ocean successfully.

Amundsen and fellow crewman Oscar Wisting who accompanied him to the South Pole in 1911 were the first men to have reached both the North and South Poles.

Fram Museum in Oslo: The Essentials

What: Visiting the Fram Museum in Oslo and learning about polar exploration.

Where: We stayed at Scandic Vulkan Hotel, a contemporary and eco-friendly hotel in the vibrant neighbourhood of Vulkan, not far from the centre of Oslo. The hotel is Norway’s first Energy Class A hotel – meaning that it generates almost all of its own energy.

The stylish rooms have floor to ceiling windows providing views across the surrounding neighbourhoods while the breakfasts – complete with waffle maker and cappuccino machines – are bountiful!

Atlas & BOots

Right next door is the Mathallen food hall with a range of boutique restaurants and bars as well as the river Akerselva, perfect for post-breakfast walks.

When: I’ve visited Oslo in the summer and autumn and like most European cities, it can be visited year-round. However, for the best weather, spring and summer (May to August) are the best times to visit. Norway’s weather is as bad as Britain’s, so out of season you can expect the days to be cold and wet beneath dark skies.

From late autumn, the ferries stop running, meaning buses are the only alternative. Although regular, the buses are nowhere near as enjoyable as the ferries and offer far more mundane views.

How: The Fram Museum in Oslo is located at Bygdøy, a short bus or ferry ride from the city centre. The ferry, which runs from early April to early October, leaves from Pier 3 behind the City Hall (Oslo Rådhuset) and takes 10-15 minutes. If the ferry isn’t running, take the number 30 bus instead. This can be boarded at the quayside near the City Hall or from the city centre and takes around 15 minutes.

Scattered across the Bygdøy peninsula there are several other noteworthy museums including the Kon-Tiki, Norwegian Maritime, Viking Ship and Norwegian Folk museums. All are within a 15-minute walk of each other.

With this in mind it’s worth buying an Oslo Pass which includes free entry to more than 30 Oslo museums and attractions as well as free travel on all public transport. The pass comes in three denominations:

24 hours: 335 NOK (40 USD)

48 hours: 490 NOK (58 USD)

72 hours: 620 NOK (74 USD) – we opted for this one

We flew from London to Oslo via a budget airline. Book via Skyscanner for the best prices.

Oslo is served by three airports: Gardermoen, Torp Sandefjord and Rygge. We recommend using Gardermoen if possible as the other two are further out and require a longer and more expensive transfer. All airports are served by trains and buses. More information can be found on the Visit Oslo website.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…