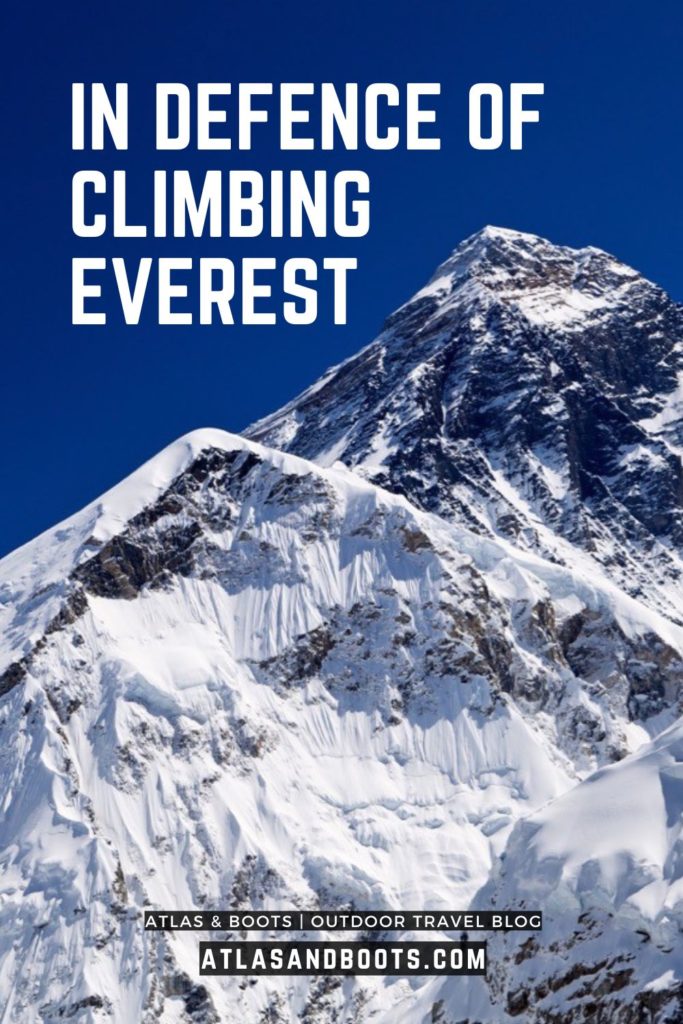

The reality is I’ve probably already hit my mountaineering ceiling but climbing Everest will always be the apex of my ambition

It has been a strange year. Usually, press trips, treks and working holidays mean it’s not uncommon for me to spend up to three months away from home. This year, however, I’ve been away just twice. This year, it was all about one thing: Denali.

I had joked with friends that over the 18 months leading up to the climb, my life had essentially been segmented into two epochs: BD (Before Denali) and AD (After Denali). I trained relentlessly, sunk thousands of pounds into the expedition and spent hours tying and retying knots, hitches and prusik loops in ropes strung out across my living room. In June, I finally climbed Denali. BD was over. AD had arrived.

But what next? I was one step closer to my ultimate goal of climbing the seven summits, the highest mountain on every continent. Denali was my fourth of the seven – arguably my fifth if you count Kosciuszko – leaving me Vinson in Antarctica and Everest in Asia (I also hope to summit Puncak Jaya in Indonesia to complete the two separate versions of the seven summits list).

In theory, when I came off the slopes of Denali, it would have been the perfect time to sign up for an expedition to Everest. I was fit, mountain-hardened and, thanks to Denali’s freezing temperatures, now owned most of the gear required for a summit of the world’s highest peak. The problem is I was broke.

I’m extremely privileged to do the job that I do and you won’t hear me complaining about my lot in life – I’m luckier than most people on this planet. That said, I’m not from a rich family, I don’t have a trust fund and I don’t have a high-powered job, so climbing Denali has stretched me financially. It’s going to take some time for me to get back in the black.

The reality is, with the cost of climbing Everest coming in at around $50,000 and Vinson the same, unless I win the lottery, I can’t see how I’ll ever have enough money to climb another seven summit. But I can still dream.

I have said before that I would rather harbour dreams I won’t achieve, than nurse none at all. However, there are other things to consider. It is fair to ask if it is still ethical to climb Everest.

On climbs, the topic of Everest regularly comes up and I’ve met several Everest summiteers during expeditions. I’ve heard people say that they aren’t interested in climbing the world’s highest peak because it has become too commercialised or overcrowded or they are put off by the garbage. Some have also said they think the risk is simply too high and the reward of standing on top of the world is not worth putting your life in danger for.

These are fair arguments. Interest in climbing Everest has increased over the last decade, as the proliferation of fixed ropes and bottled oxygen has made the mountain easier to climb and there are more climbing outfits working on the slopes than ever before.

In 2023, a record number of climbing permits were issued in Nepal. According to Nepal’s Department of Tourism, the agency issued 421 permits to foreign climbers in 2024 – down from 478 in 2023 – and approximately 600 people reached the summit, including climbers, guides and assistants. The year 2023 was also the deadliest climbing season on Everest with 18 climbing deaths recorded (the 2015 earthquake caused more deaths on the mountain but not all were climbers).

However, I am uneasy about calling out a developing country for making use of its natural wonders. It feels particularly paternalistic coming from a western standpoint. Nepal’s Sagarmatha National Park is nowhere near as commercialised as the mountain areas of Europe or North America. If Everest were in the western hemisphere, I expect it would be busier and far more commercialised.

Over 20,000 people climb Mont Blanc, western Europe’s highest peak, every year. At the height of the climbing season, 200 climbers a day attempt to reach the summit leading to overcrowding and carelessness with up to 100 climbers dying on Mont Blanc each year, making it one of the world’s deadliest mountains. In 2007, a team set up a jacuzzi on the summit of Mont Blanc.

In the UK, a train runs to the summit of Wales’ highest (and busiest) peak. In the Alps, there are hotels on the top of mountains (the irony of Hotel Grawand’s tagline ‘nature only’ seems completely lost on marketers). Throughout Europe and North America, ski resorts blanket the slopes and valleys of mountain ranges causing untold damage to ecosystems. Some ski resorts now use snow machines and fleece blankets to negate the damage they’ve caused through decades of rampant commercialisation.

In 2022, 57,690 tourists visited Sagarmatha National Park where Everest is located. During the same period, over two million people visited Switzerland’s renowned resort of Zermatt, home to the iconic Matterhorn. Zermatt municipality occupies around a quarter of the area of Sagarmatha National Park. Glass houses springs to mind.

For me, concerns about trash and the environmental impact of climbing Everest are a more justified argument against climbing the mountain. It is estimated that more than 50 tonnes of waste and over 200 bodies are on Everest. This year, a Nepal government-funded team of soldiers and Sherpas removed 11 tonnes of garbage, four dead bodies and a skeleton from Everest during the climbing season. The lead Sherpa reported that it could take years to properly clean the mountain considering the challenges. But there is precedent.

Denali, which receives similar numbers of climbers to Everest, albeit for shorter periods, also struggled with waste left on the mountain. Clean climbing practices on Denali have evolved over the past 30 years which has seen a successful ‘pack in-pack out’ policy beginning in the late 1970s, with climbers removing most of their garbage from the mountain.

Today, the program goes further and mandates the removal of human waste from historically contaminated areas such as the West Buttress High Camp. As such, all expeditions on Denali are supplied with several Clean Mountain Cans for climbers to use. During my climb, I was impressed by how clean the mountain was even though some of the camps were enormous and busy with climbers.

That said, despite the success of the clean-up project on Denali, it is estimated that around 66 tonnes of human faeces is still on the mountain. Again, perhaps we in the west should be mindful of hypocrisy. At least the Nepali government has recognised the problem and is addressing it. Denali proves that it can be done.

It certainly feels that recent seasons on Everest are more likely to be remembered for all the wrong reasons: earthquakes, brawls, politics, excess deaths, ignored rules, trash and even allegations of sexual misconduct.

Somehow, amidst the negative headlines, the joy and fulfilment felt by the summiteers gets lost. They worked and trained relentlessly to celebrate standing on the top of the world for only a few minutes. I’ve climbed enough mountains to know that high-altitude summits do not come easy and do not last long. The moment is over in minutes, but the memories last a lifetime. Of all the Everest summiteers I’ve met, not one of them has ever expressed regret.

This year has been tough. But for a few minutes in June, I stood on top of the highest peak in North America and felt nothing but pure elation and pride. It was worth every pound, every gym session, every missed moment and every risk. I’d do it again in a heartbeat.

And for that reason, I’m not giving up on Everest yet.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…