In 1947, Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl crossed the Pacific Ocean on Kon Tiki, a rudimentary raft made of balsa wood. We took a trip to see the legendary vessel

“Your mother and father will be very grieved when they hear of your death,” Thor Heyerdahl was told as he prepared to cross the Pacific by raft.

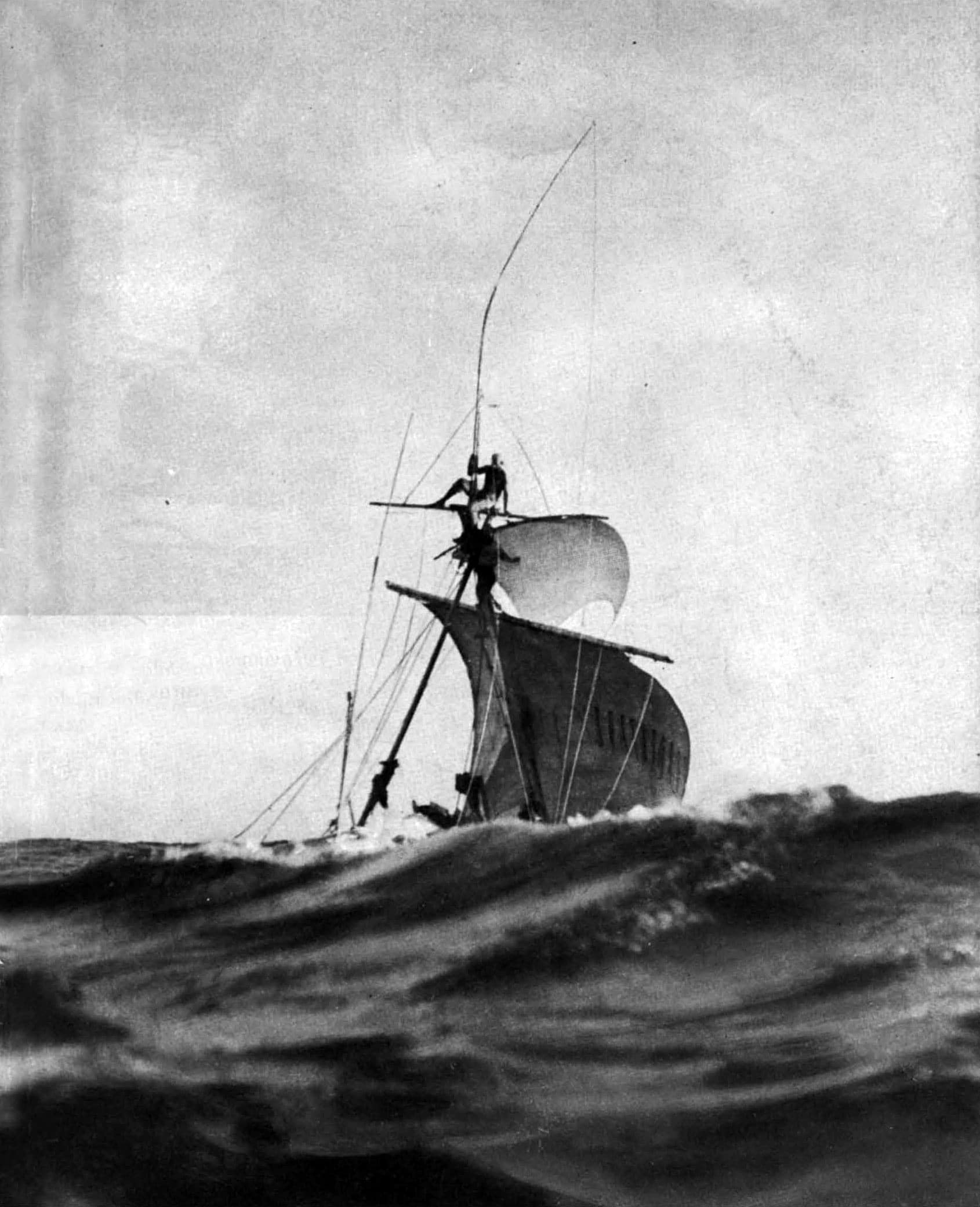

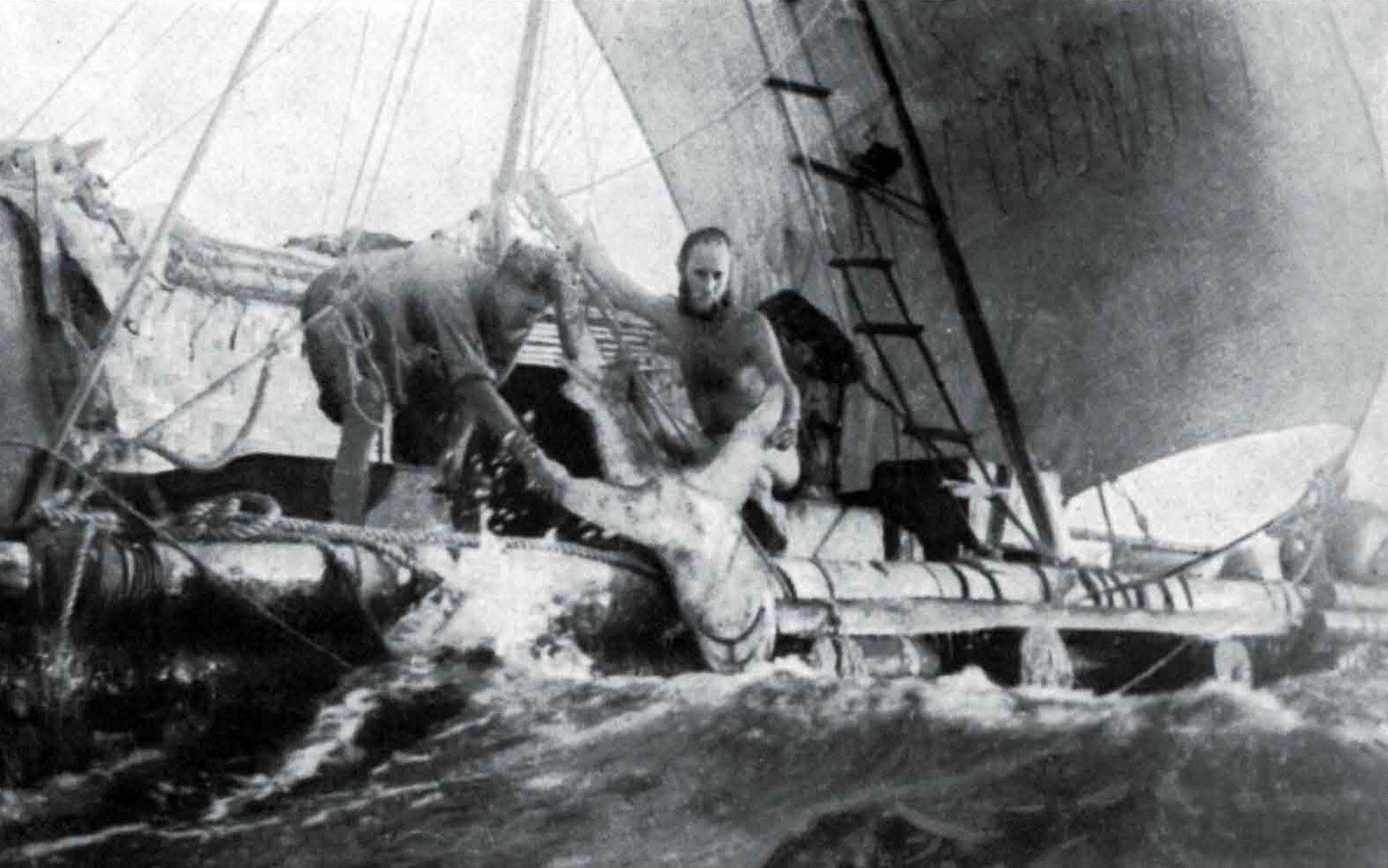

The raft’s dimensions were wrong, it was so small it would founder at sea, the balsa logs would break under strain or become waterlogged a quarter distance into sea, gales and hurricanes would wash the crew overboard, and salt water would slough the skin right off their legs – there was no end to the warnings.

In fact, according to the experts, “there was not a length of rope, not a knot, not a measurement, not a piece of wood in the whole raft which would not cause us to founder at sea,” Heyerdahl wrote in his first-hand account of the perilous journey.

And yet the Norwegian explorer persisted with his so-called suicide mission. His aim? To prove the theory that migrants from South America could have settled Polynesia in pre-Columbian times.

Critics called it impossible and warned that the makeshift rafts of pre-Incan peoples could not navigate thousands of miles of open ocean to reach the distant islands using stone age technology.

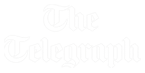

The Kon Tiki’s route across the Pacific

For the Kon Tiki expedition, Heyerdahl aimed to complete the journey using only the materials and equipment available in pre-Columbian times and in doing so to prove that such a voyage was possible. The expedition carried some modern equipment, such as a radio, charts, sextant and metal knives, but Heyerdahl argued they were incidental in proving that the raft itself could make the journey.

On an extended research trip in Polynesia’s Fatu Hiva, Heyerdahl had noted the presence of South American plants such as the sweet potato, as well as similarities between stone figures on Fatu Hiva and the structures erected by ancient South American civilisations.

He also saw similarities in the physical appearances, rituals and myths of the Polynesians and South Americans, and heard Polynesian elders speak of a demigod named Tiki who came to the islands from a big country beyond the eastern horizon.

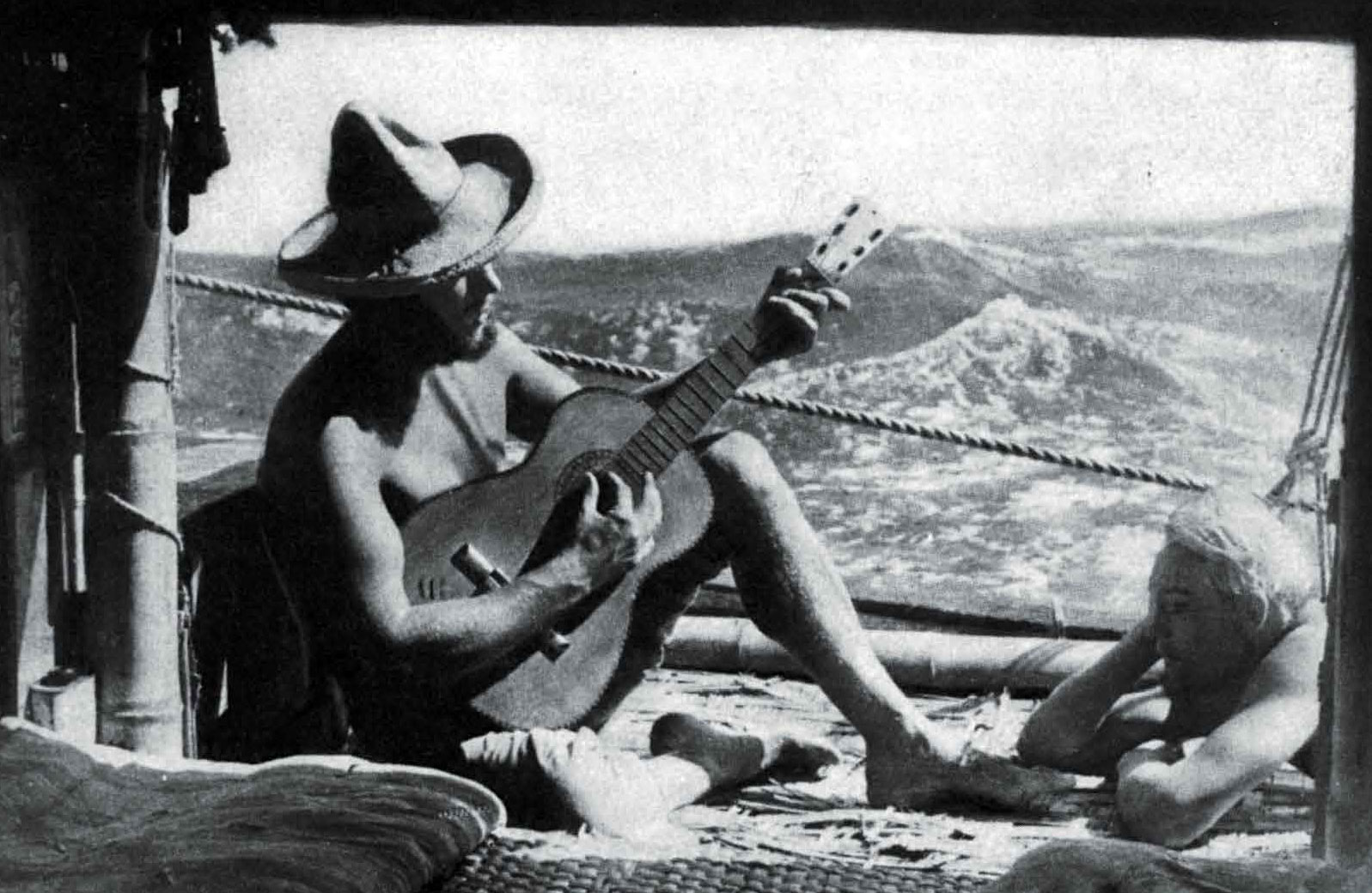

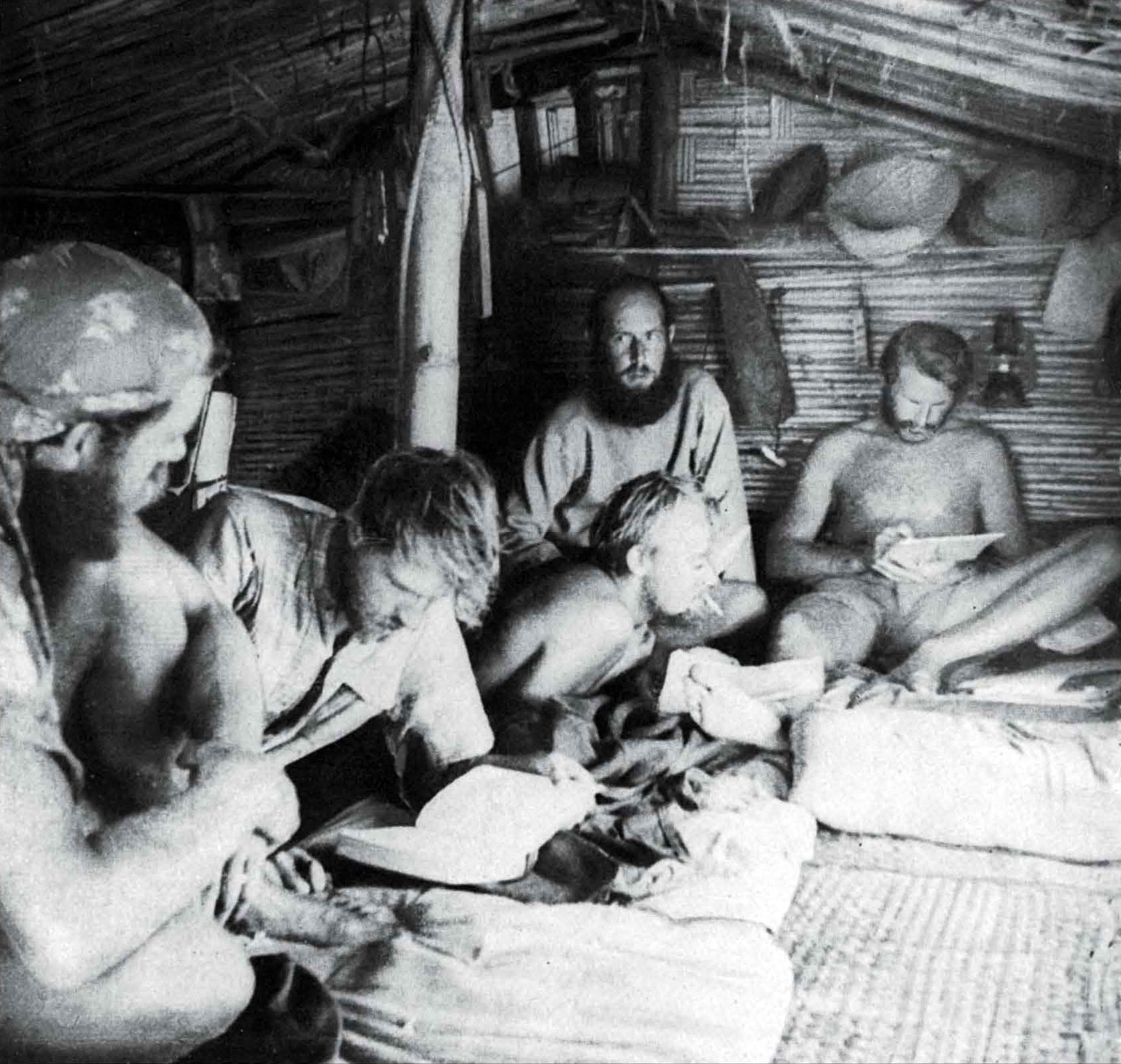

Despite his lack of sailing experience – and the fact that he couldn’t swim – Heyerdahl set out to prove that his theory was possible. He gathered funds through private loans, donations of equipment from the US army, and a crew of five men with a promise of “nothing but a free trip to Peru and the South Sea islands and back”.

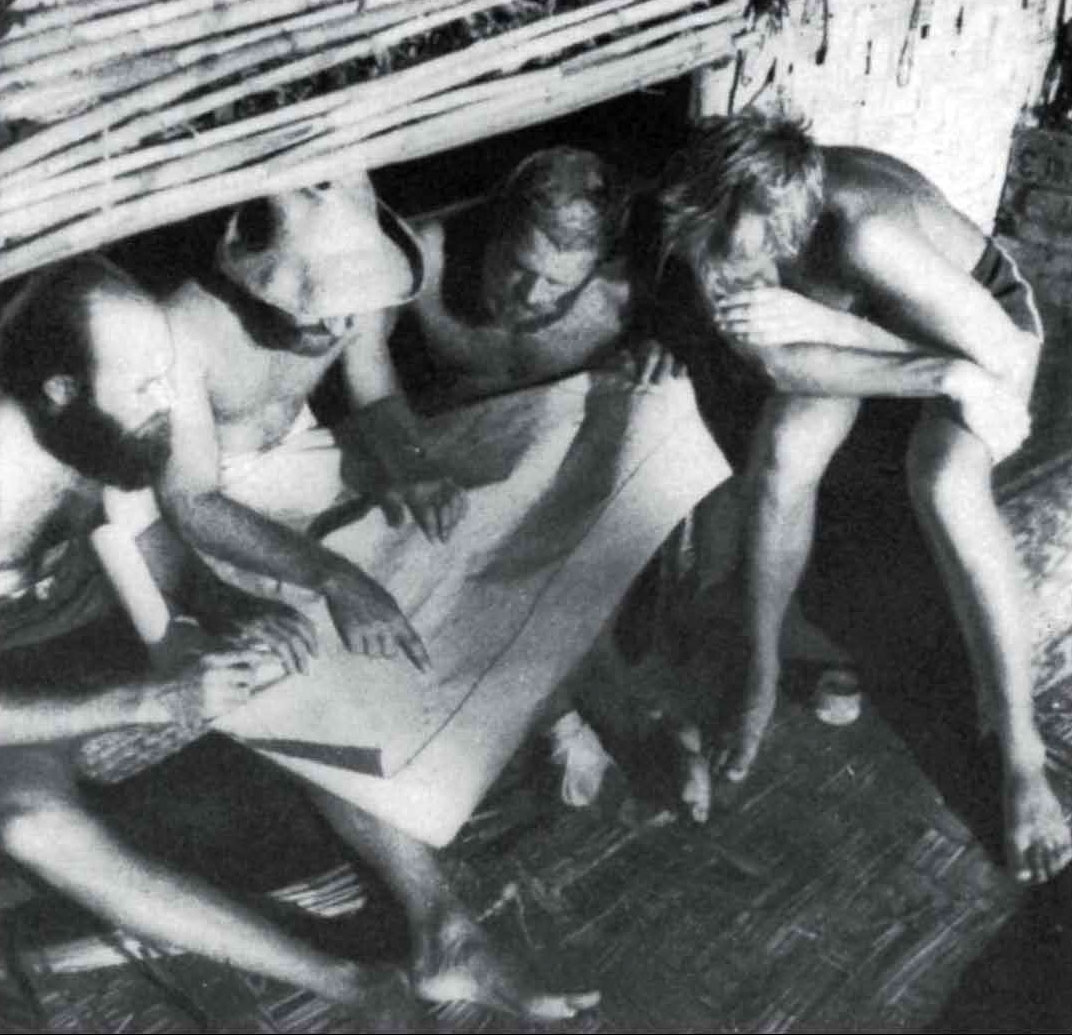

An open bamboo cabin provided Kon Tiki’s only shelter from the elements

Heyerdahl’s small team comprised Erik Hesselberg, navigator and artist; Bengt Danielsson, translator and steward in charge of supplies; Knut Haugland, radio expert; Torstein Raaby, radio operator; and Herman Watzinger, engineer.

The men journeyed to Peru and built the 30ft x 15ft Kon Tiki out of nine balsa wood logs lashed together with hemp ropes in an indigenous style recorded in illustrations by Spanish conquistadors. An open bamboo cabin with a roof made of banana leaves provided the only shelter from the elements.

With a smash of a coconut against the bow, the raft was named Kon Tiki after the Peruvian sun god who was said to have vanished westward across the sea; a mythical figure who mirrored the Polynesian demigod, Tiki, who arrived from the east.

Kon Tiki set off from Peru on the afternoon of 28th April 1947, starting its epic journey across the Pacific Ocean.

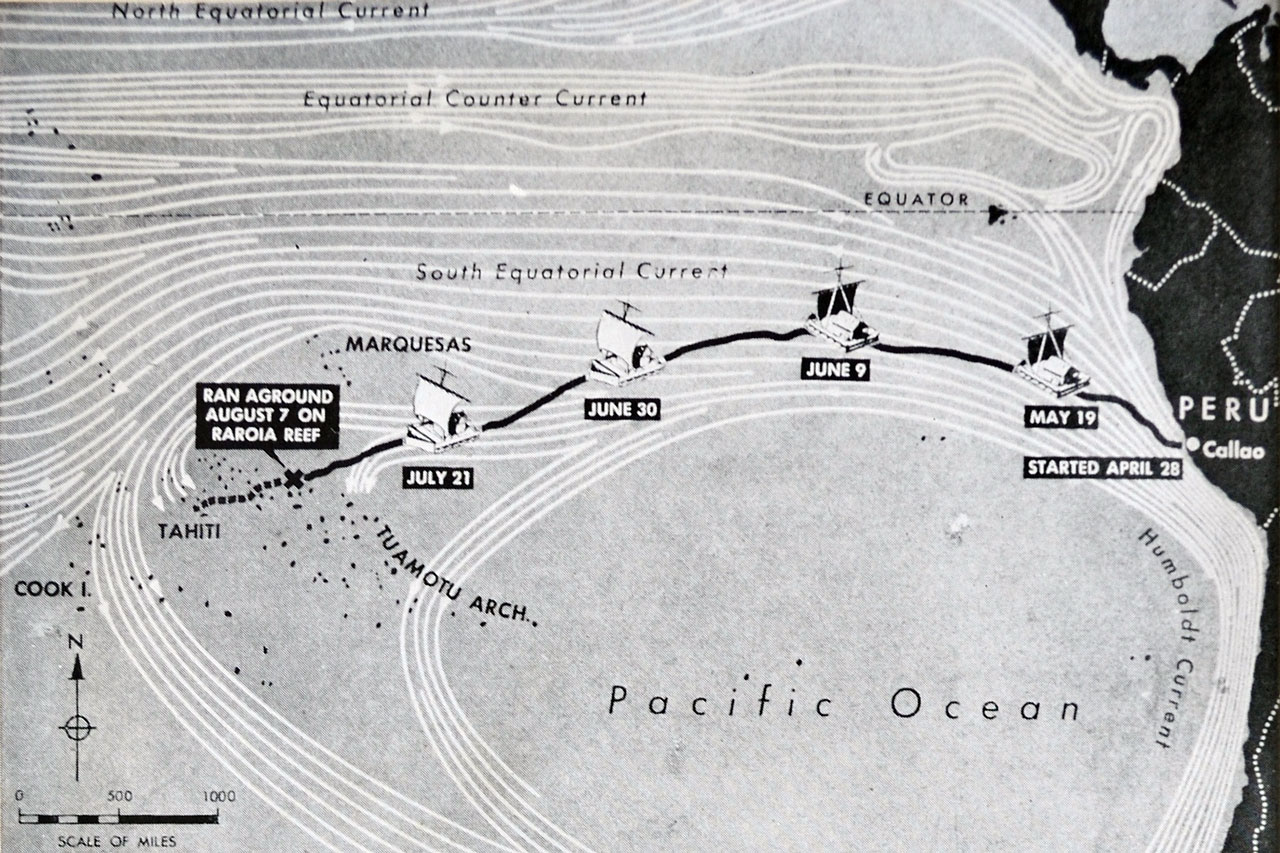

Original images of the Kon Tiki expedition

It was this legendary raft that we went to see on our recent trip to Oslo in Norway. We made the short bus journey from Oslo center to Bygdøy with its trio of museums: the Fram, the Kon Tiki and the Viking Ship Museum.

Peter, being a Polar exploration junkie, most looked forward to seeing the Fram. I, having read Heyerdahl’s book several years earlier, was more excited to see Kon Tiki.

We unwrapped our many layers in the foyer of the Kon Tiki Museum and made our way straight to the main attraction. There, in muted light, stood the vessel of legends.

I stared at it for a minute feeling surprisingly unmoved. It seemed unreal somehow: a replica or a cartoon version of something more serious. I double checked and confirmed that it was indeed the original raft. It looked too clean, too intact.

The main attraction at the Kon Tiki Museum

I walked around the raft, trying to conjure images of the six men navigating by the sun and stars, guided by winds and currents as they beat against waves that towered above their masts. Given their remote location, rescue would have been near impossible.

As I stood there next to Kon Tiki, my impassivity was perhaps best explained by the surrealism of it all. Heyerdahl and his men sailed for 101 days across 6,900km (4,300mi) of the Pacific Ocean. I’ve seen about the same distance of the same ocean and couldn’t quite fathom how they did it in a makeshift raft with stone age technology.

After 101 days at sea, Kon Tiki crashed onto a reef on Raroia island on 7th August 1947.

The men were greeted by locals from a nearby island who arrived in canoes after spotting flotsam from the raft. Heyerdahl and his men were taken to Tahiti – the salvaged Kon Tiki in tow – and were soon enjoying international acclaim for successfully completing the journey and proving that Heyerdahl’s theory could indeed be right.

Sadly, in later years, linguistic and genetic research proved that Polynesia was settled by peoples from Asia who arrived in an eastward migration. Heyerdahl had thought it impossible that the navigators would set sail against prevailing winds.

In truth, it was exactly the fact that they could use the westward wind to safely return home in event of failure that encouraged these ancient explorers to sail into the Pacific abyss.

That it was difficult to reconcile the vessel in the museum with Heyerdahl’s legendary journey speaks to the magnitude of his accomplishment. It may be impassivity that I felt first but seeing Kon Tiki in the flesh reminded me of the courage of the explorers of our past.

Even though there is little left of the world to discover, there is much of it still to explore and we’d all do well to draw deep on our courage and try something new even when there’s a good chance we’ll fail.

Kon Tiki Museum: The Essentials

What: Visiting the Kon Tiki Museum in Oslo and seeing the legendary raft that crossed the Pacific Ocean.

Where: We stayed at Scandic Vulkan Hotel, a contemporary and eco-friendly hotel in the vibrant neighbourhood of Vulkan, not far from the centre of Oslo. The hotel is Norway’s first Energy Class A hotel – meaning that it generates almost all of its own energy.

The stylish rooms have floor to ceiling windows providing views across the surrounding neighbourhoods while the breakfasts – complete with waffle maker and cappuccino machines – are bountiful!

Right next door is the Mathallen food hall with a range of boutique restaurants and bars as well as the river Akerselva, perfect for post-breakfast walks.

When: For the best weather, spring and summer (May to August) are the best times to visit Oslo. Out of season, you can expect the days to be cold and wet beneath dark skies.

From late autumn, the ferries stop running, meaning buses are the only alternative. Although regular, the buses are nowhere near as enjoyable as the ferries and offer far more mundane views.

How: The Kon Tiki Museum in Oslo is located at Bygdøy, a short bus or ferry ride from the city centre. The ferry, which runs from early April to early October, leaves from Pier 3 behind the City Hall (Oslo Rådhuset) and takes 10-15 minutes.

If the ferry isn’t running, take the number 30 bus instead. This can be boarded at the quayside near the City Hall or from the city centre and takes around 15 minutes.

Scattered across the Bygdøy peninsula there are several other noteworthy museums including the Fram, the Viking Ship, the Norwegian Maritime and Norwegian Folk museums. All are within a 15-minute walk of each other.

With this in mind it’s worth buying an Oslo Pass which includes free entry to more than 30 Oslo museums and attractions as well as free travel on all public transport. The pass comes in three denominations:

24 hours: 335 NOK (40 USD)

48 hours: 490 NOK (58 USD)

72 hours: 620 NOK (74 USD) – we opted for this one

We flew from London to Oslo via a budget airline. Book via Skyscanner for the best prices.

Oslo is served by three airports: Gardermoen, Torp Sandefjord and Rygge. We recommend using Gardermoen if possible as the other two are further out and require a longer and more expensive transfer. All airports are served by trains and buses. More information can be found on the Visit Oslo website.

For more things to do in Oslo get the Lonely Planet Guide to Norway.