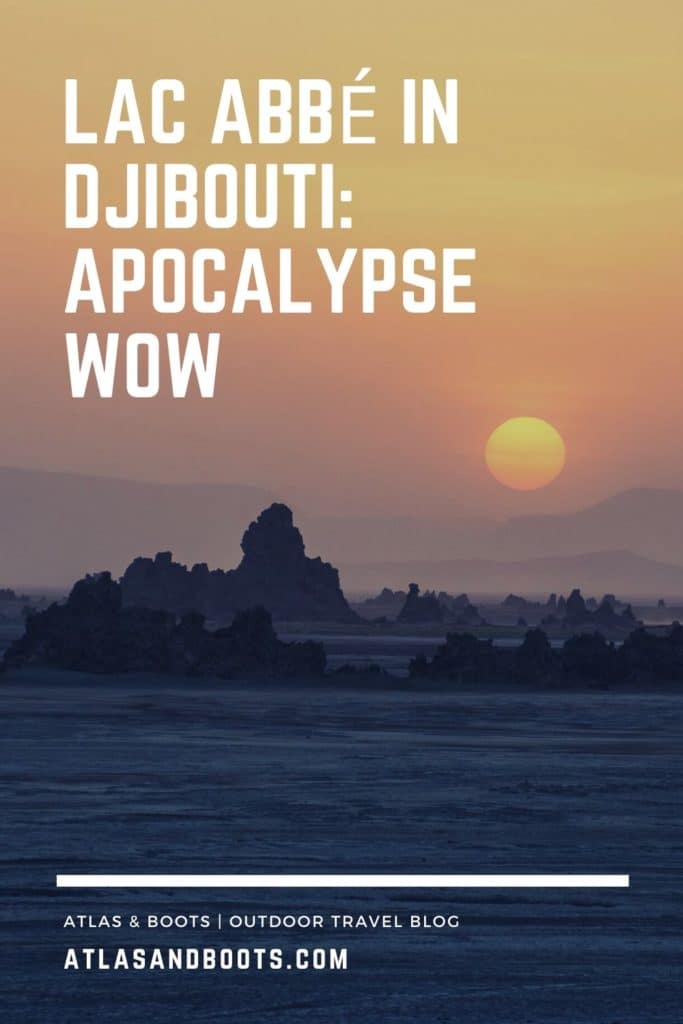

Lac Abbé in Djibouti is both desolate and apocalyptic. Seeing this eerie moonscape is a surreal experience like little else on Earth

It turns out that the 1968 film Planet of the Apes was not filmed in Lac Abbé in Djibouti, as proudly claimed by several guidebooks, numerous blogs, countless Djiboutian tour guides and even international newspapers. The producers didn’t even leave the Western United States.

This is a crying shame firstly because Lac Abbé is a suitably apocalyptic filming location and secondly because there goes Djibouti’s only claim to fame.

Before Lonely Planet named Djibouti as one of their best countries to visit in 2018, I would have struggled to point to this tiny speck of a nation – one-sixth the size of England – on a map. Stationed in the Horn of Africa among some fairly dubious neighbours, it is home to some of the strangest landscapes we’ve seen – Lac Abbé being one of them.

Located 140km southwest of Djibouti City on the Ethiopian border, Lac Abbé may as well be on another planet. The salt ‘lake’ is positioned on a plain known as the Afar Triple Junction. Here lies the central meeting place where three divergent segments of the Earth’s crust – the African, Somalian, and Arabian plates – are tearing apart from each other.

It is this feature that defines and influences the strange topography of the Afar Depression. Just across the border in Ethiopia, more otherworldly phenomena dot the landscape of the Danakil Depression including the Dallol sulphur pools and Erta Ale volcano.

The only practical way of visiting Lac Abbé is by 4WD from Djibouti City. We joined an organised tour with Rushing Waters Adventures and left the city in the morning to cut across the country towards the border.

En route, we stopped at the Grand Bara Desert, just another of Djibouti’s many freakish panoramas. Stretching for miles in every direction, cracked clay – all that remains of dried-up lake bed – forms a vast arid plain in the centre of the country.

After a short stop for lunch in the forgettable town of Dikhil, we left sealed road to steam across the desert. Small villages popped up here and there, literally rising from nowhere. We paused at one along the way to stretch our legs and quench our thirst.

Incomprehensibly, life does somehow prevail out here. The Afar people have established settlements in this seemingly barren land where they keep livestock and dig wells to access water.

Closer to the lake shores, there are pockets of marshland which provide some grazing for their livestock. The Afar, being a nomadic people, make full use of these pockets, leading their grazing goats back and forth from the shore.

Despite these pockets, one thing there isn’t much of at Lac Abbé is water. The lake may be the final destination for Ethiopia’s Awash River, but its arid landscape absorbs nearly all of the water. Instead, a thin, shallow layer of sultry water stretches on hauntingly like a sheet of inhospitable grey.

After our stop at the village, we headed back to the 4WD to continue our journey. We wound through rugged embankments before emerging suddenly onto the basaltic plateau of Lac Abbé.

The plateau is not featureless. Rather, it is dotted with hundreds of limestone chimneys, some standing 50m (160ft) high and belching puffs of steam. To add to the already dystopian landscape, there are hot springs that fracture the earth and intermittent dust storms sweeping across.

We wandered amid limestone chimneys and twisted, tortured, cork-screwing pinnacles that rose sharply from the dusty plain. As the light began to fade, a typically inflamed African sun descended and the moonscape became Martian.

It felt indeed like witnessing the apocalypse. Soon, dusk settled and we continued on to our camp for the night, safe in the knowledge that the sun would rise again and we’d see the whole scene unravel in reverse.

After camping in the Danakil Desert in Ethiopia we didn’t have high hopes for this equally remote corner of Djibouti, but we were delightfully surprised.

The camp was clean and had toilets, showers, running water and electricity. Our traditional Afar huts resembled armadillo shells and came with mattresses and mosquito nets – all relative luxury compared with what we’d experienced across the lake in Ethiopia.

We slept comfortably (if somewhat slathered in mosquito repellent) and rose early to catch the sunrise and explore the landscape more closely. We drove deeper into the terrain and parked up to inspect the different topography underfoot.

In places, boiling springs bubbled and steamed up through chasms in the ground. Elsewhere, pockets of groundwater lay stone still, reflecting the eerie scene around. Wild boars trotted across the greener parts of the plain.

After our morning exploration, we returned to camp for breakfast before climbing into our 4WD for the journey back towards the coast in pursuit of Lac Assal, another unique landscape. Djibouti may be small, but what it lacks in size it makes up for in… well, weirdness.

It doesn’t matter that Planet of the Apes wasn’t filmed here. It could very well have been.

Atlas & Boots

Lac Abbé in Djibouti: the essentials

What: Visiting Lac Abbé in Djibouti as part of 2-day, 1-night tour of Lac Abbé and Lac Assal.

Where: We stayed overnight at an Afar camp which was surprisingly comfortable (running water, western toilets with bidets and electricity!).

Afterwards, we returned to the Sheraton Djibouti which overlooks the Red Sea. Rooms are clean and comfortable with excellent wifi and pretty sea views on one side of the hotel. The outdoor pool is nestled on a raised platform above the sea giving the distinct feeling of being aboard a boat.

Atlas & Boots

The hotel offers a range of amenities including a free airport shuttle, a shop stocked with essentials, a business centre and fully-equipped fitness centre. Naturally, we preferred the comfy lounge area, perfect for enjoying a whisky sour in the evening and watching the sun set over a gently lapping sea. Overall, it was a welcome touch of comfort with which to end our trip.

When: The best time to visit Djibouti is Nov-Jan when whale sharks make their annual visit and the weather is cooler. The shoulder seasons of Oct and Feb-Apr are also good times to visit. May-Sep is extremely hot.

How: We visited Lac Abbé in Djibouti on a 2-day tour with Rushing Waters Adventures, currently ranked the number one company in Djibouti on TripAdvisor. Rushing Waters is operated by Wisconsin native Ken who has lived in Djibouti for over seven years (and can even speak Somali!).

Our tour was well organised and, as mentioned above, the overnight camp was surprisingly comfortable. The tour includes pickup and dropoff, all meals and non-alcoholic drinks, a driver for two days and accommodation for one night.

Overall, it’s an excellent way to visit these otherworldly landscapes. Book via Ken at Rushing Waters Adventures: www.kayakdjibouti.com, kgradall@kayakdjibouti.com, +253 77 79 49 58.

Djibouti is a small country which means it’s fairly easy to get around. Taxis from the airport charge set fares to hotels in the city (approx 2,000 DJF / $11 USD). Check the board outside the airport to make sure you don’t get overcharged. Some hotels including the Sheraton operate free shuttles, so check beforehand.

Book international flights via skyscanner.net for the best prices.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…

To find out more about sights such as Lac Abbé in Djibouti, we recommend the Lonely Planet Ethiopia & Djibouti guide – ideal for those who want to both explore the top sights and take the road less travelled.