In her new book, Miriam Lancewood explores the relationship between humans and nature. Here, she tells us about the travel that changed her

Miriam Lancewood has not lived a conventional life. She and her husband, Peter, spent seven years in the wilderness of New Zealand during which time they survived by hunting wild animals and foraging while sleeping in a tent and cooking on an open fire. Since then, Miriam has walked across Europe and written three books about her experiences in nature.

Miriam was born in the Netherlands in 1983. After finishing university, she worked for a year in Zimbabwe before travelling to India where she met Peter – an encounter that would change their lives forever.

After journeying for years through the great ranges of Asia, they eventually found themselves in Peter’s native New Zealand. In 2010, they sold or gave away nearly all of their possessions and struck out on a bold off-grid experiment.

For seven years, Miriam and Peter lived a nomadic life in the wilds of the New Zealand Alps. After returning to civilisation, they walked across Europe to Turkey with a tent and little else before finally settling down in Bulgaria.

Miriam’s 2017 memoir, Woman in the Wilderness, became an international bestseller and was translated into five languages. The sequel, Wild at Heart, was released in 2020.

Here, she tells us about Wilder Journeys, her new book in which an extraordinary collection of authors share their own profound experiences in nature.

Your new book, Wilder Journeys, looks at mankind’s relationship with nature. Why is this important?

If we look at the evolution of mankind we see that humans have moved from using instinct to relying on more and more complex and abstract thinking. So much so that we live in ‘hyper-reality’ and are barely aware that we have a body. The physical world and our physical body have become almost irrelevant. Our digits in the bank and social media status are much more important to us.

Since our body is irrelevant, it’s easy to forget we need more sleep, less stress, to eat healthier or breathe better air. Since the natural world is irrelevant, it’s easy to forget (and sometimes even hard to notice) that we destroy the soil and the forest and have polluted the rivers, oceans and air.

If we reconnect with our body, we begin healing. If we reconnect with our environment we stop the destruction. The two are entirely linked. We have to move from our heads into the actual world we live in.

Is there a particular story from the book that resonated with you?

The story of Karl Bushby was impressive. The fact that he had been walking for so many years (and still is walking!) is incredible. I could see myself joining all of the other authors, but I’m not so sure if I’d have had the courage to go through the Darien Gap like Karl.

Reading his chapter made me think, could I actually handle that situation? Or would I collapse and give up?

What made him face his fears and enter that very hostile and dangerous environment? Because of his extended army training and experience? Or has he trained his mind to overcome the fear of death, and this made him able to live like a tightrope-walker?

Reading his story was highly inspirational because I believe that if he could survive all that, then maybe I could too.

On page 87, we included an excerpt from The Hunter-Gatherer Way by Ffyona Campbell.

“…we [Mankind] had once known what it felt like to be no greater and no lesser than anyone else. It gave me such a huge sense of relief when I realized that we don’t have to rule the world at all, it all works very well, all by itself.”

Ffyona Campbell

This sentence speaks to me. I felt the same when roaming for seven years in the wilderness of New Zealand. We lived in places humans had never settled. We discovered valleys man had never set foot in. It was comforting to know that those untouched places still exist and continue to exist into the eternal future. Some things will never change, whether we think we rule the world, or not.

You spent seven years living in the wilderness. What was the hardest part of the experience?

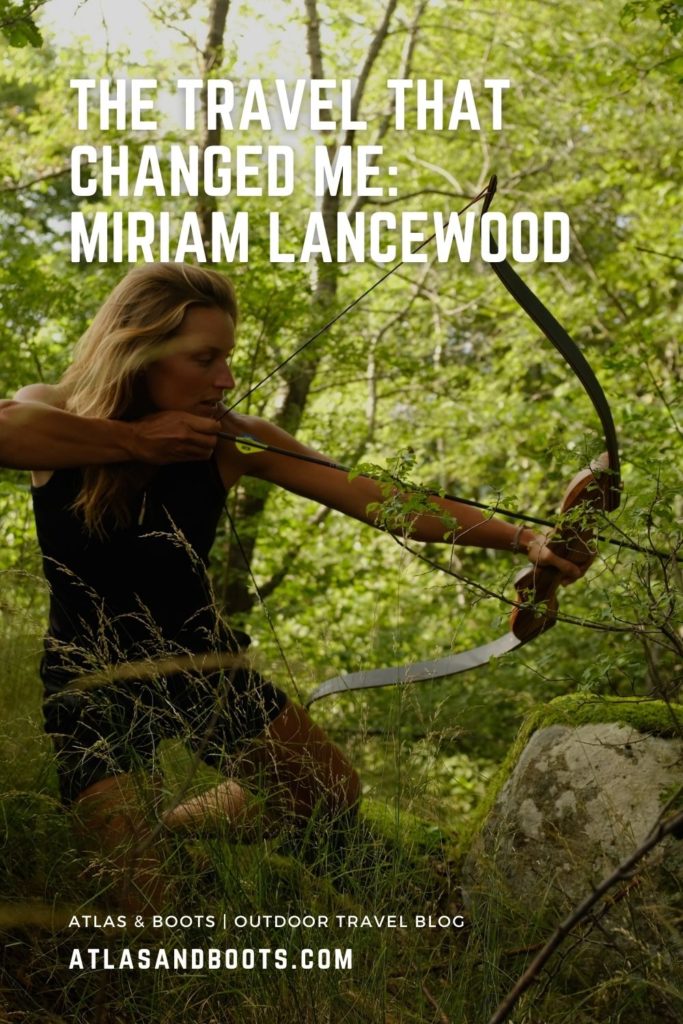

The hardest part of living in the wilderness was learning how to hunt. I had practised archery on a target before we set out. After 12 months, I thought I had mastered shooting and I believed I could hunt.

Unfortunately, I failed utterly in our first winter. We had set out to live off hunting and gathering and yet I always came back empty-handed. In the end, I didn’t believe I could do it. I was so disappointed in myself. We had done our training and preparation for more than a year and when we finally set out to live in the high mountains in a tent, I failed at supplying food. I felt such a failure.

Luckily, we could trap and eat the brushtail possums. Otherwise, we would have grown very hungry and we would have lost too much weight to continue living in the wild. Only after six months did I shoot my first goat.

It was a good lesson: you will only master a new skill by many errors. Success only comes through patience and perseverance.

But this arduous process also gave me much confidence: if I could learn how to hunt, I could also learn to grow vegetables, cure skins to make garments, build a hut, learn a new language, or learn how to write a book.

Another unexpected challenge in that first year was to learn to do nothing. There were quite a few days (after we had trapped a possum and gathered firewood) when there was little to do. We felt restless and realised that we had to slow down. We had left a busy life behind. I had been working as a teacher, we saw many friends. It was a shock to suddenly have so little stimulation. We had left all technology behind (on purpose). We did not even have a clock. We wanted to really connect with the timeless wilderness and knew that a device would influence the way our minds would experience the natural world.

We discovered we had to go through a period of boredom. We were forced to face boredom and wait until it ebbed away (rather than finding activities to cure the boredom), in order to meet with the rhythm of the natural world.

Only after three weeks, we felt we had slowed down. Only then did we feel really at ease in the forest; we felt happy just sitting and watching the world. We had become part of nature rather than just an observer.

What region or trip has impacted you the most?

My life changed drastically when I met Peter in South India. I had intended to travel for a year in India on my own. After five months, I met Peter. I was 22. He was 52.

That day in January 2006 was the best day of my life. It was the beginning of an authentic and adventurous existence. He stressed the importance of ‘doing something different’. ‘Use your creativity to live authentically,’ he’d say with a smile. ‘If you understand the symbol of money, you can live without working in a job.’

Those courageous ideas sounded radically exciting to me. I discarded the objection ‘he is too old for me’ and I followed him into the mountains. Our first big adventure together was a journey through the Himalayas.

Peter was very experienced and understood the region well. He knew that we should travel light. He had observed the Gaddi shepherds who carried only woollen blankets and a bit of chapatti flour. Peter maintained, ‘They are humans and we are humans. If they can do it, so can we.’

And after three months of altitude training around Dharamshala, we set out and walked for two months to Ladakh. We had no tent or cooking gear. We just had a pair of sandals, a summer sleeping bag and a thin mat. In Zanskar, we ate tsampa like the Tibetan yak nomads we met along the way. We slept under the Milky Way, we climbed the mountains using nothing more than a rhododendron walking stick.

It was the most amazing journey I completed in my life. Those huge mountains transformed my mind. We are tiny, I realised. We are insignificant. Pray to Shiva or you’ll fall off the mountains.

Who decides if I will live or die? The gods or the mountains, the wind or I? I realised that there’s quite another mystery at work that sustains life.

Do you still have a dream destination you haven’t yet visited?

Yes, I’d like to return to those Himalayan mountains this summer. Unfortunately, Peter is unable to come with me. Five years ago we were travelling in the outback of Australia. He contracted a stomach bug, then severe diarrhoea with dehydration as a result. In the hospital, they diagnosed him with acute kidney failure.

When he didn’t recover, the doctor told him it was chronic. Without dialysis, he’d have little chance to survive. After weighing up the pros and cons, Peter stated he’d rather die than move to town and commit to dialysis treatment.

Miraculously, his kidneys recovered enough to have a happy life in the Rodopi mountains of Bulgaria. Walking with a heavy backpack is history for him now, but we are using our creativity to think up new adventures for the future.

This summer, I will go with a small team of authors from Wilder Journeys into the Himalayas for two months. Our expedition leader will be Sophie Hilaire who has summited Everest.

I’d love to see those high peaks again. Nowhere in the world have I seen stars as bright as in the thin air of Zanskar and Ladakh. We are planning to hike over three 5000+ meter passes near the Spiti Valley. We’ll go without porters or guides. We will go as light as possible, but this time I’d feel more comfortable with a tent and a billy-pot to boil some tea.

In some parts of the journey, we will not see any villages, so we have to carry more food. It will be a tough challenge.

Right now, Peter and I are living in our off-grid shepherd’s cottage in the Rodopi mountains in Bulgaria. I’m training every day for the Himalayas. I have put big stones in my pack and I’m walking up and down steep mountains. Every second day I’m going for a run. When I light the fire outside to cook the food, I try to squat as long as possible. When waiting for the water to boil I’m standing on one leg to train my balance. I do pull-ups from a branch in a tree. Before I go to bed I do push-ups and sit-ups. Call it an obsession, but I know what it is like to climb 5,000m mountains with little oxygen.

Are you a planner or a see-how-we-goer?

Both. My saying is: think up the most ridiculous journey and plan everything rationally and thoroughly.

I ask myself: what gear will I use, what skills do I practise, what advice do I need, what food supplies will we buy?

Once we set out, we are subject to the weather, the flooded rivers, the mountains and other people. Then we can not time-manage our journey any longer. Then we rely on our preparation. Then we see how we go.

Unexpected meetings, insights and experiences are the most valuable to me. We call it randomness. To me, randomness is magic.

People think that living in the wilderness is a chilled-out existence. But the reality is that you need to have your shit together. Before the rain comes, you need a stack of dry firewood. Get everything ready for the night before it’s dark. Never go on a hike without a woollen jumper and a raincoat – no matter how blue the sky looks. Wash when the weather is good and clean your clothes on sunny days. Remember where you put that spoon. Put every item back in the right place. As we only have a few belongings, we learned to look after them.

Hotel or hostel (or camping)?

The best nights I have is when we pitch our tent in the forest. We feel safe. It’s quiet. It’s free. And we sleep very well. There’s a soft breeze in the leaves, fresh air and the birds at dawn. When we wake up, we feel refreshed.

We usually avoid countries where wild camping is illegal. But in 2017 we walked for four months on the E4 walkway in France, Switzerland, Germany and Austria. Freedom camping was officially illegal there, but we discovered that no one ventures off the beaten track. It didn’t occur to people that there were two secret campers in their forest. We always cooked our meals on fires. We learned how to avoid smoke by using dry willow wood.

A few times we ended up in a hotel in a city. We couldn’t sleep for the noise of the fridge, washing machine, air-conditioning or whatever. There are so many buzzing machines everywhere. We wanted to open the window for some fresh air, but the traffic noise was too loud.

When sleeping for years in a tent in the forests and mountains, we learned to be alert at night. Noise can mean danger. It’s a matter of survival to sleep lightly. This skill backfires in the city. There are too many noises that wake you up.

To guidebook or not to guidebook?

No guidebook. We always ask people. Needing help or advice is always a good reason to connect with the locals or other travellers. Nowadays you see everyone looking at their phone. It’s much better to ask someone the way. The person might just give you a lift, invite you inside, make you taste some local food, give you priceless information, or offer an unforgettable experience. Unexpected beautiful moments happen when contacting strangers.

When travelling into pure wilderness, where we will definitely not see any humans, we take maps. Getting lost is not a good idea. It’s important to know where you are.

Do you count countries?

I did count once when a friend asked me how many countries I had been to. But I think a quick stopover in Seoul is quite different from spending one year in Zimbabwe. So a number alone can be quite misleading.

I rather count passports. So far I have a Dutch passport that gives access to the EU and a New Zealand passport, which allows me to live indefinitely in Australia as well. We also obtained Bulgarian residency.

I do like to visit as many countries as possible, but I’m more interested in living in a foreign country. You need at least a couple of years before you understand the culture and language. By moving to a new place you get out of your comfort zone. Moving keeps your mind young and flexible. Being nomadic keeps you agile.

We have been in Bulgaria for almost two years. We walked through this country, saw a beautiful little cottage in the forest and we managed to buy it. It’s a beautiful region with few rules. You can camp anywhere and light a fire anywhere you like. The government assumes you are a responsible and honest person. I appreciate that attitude.

It’s nice to be in East Europe, but we are also very attracted to Central Asia. We are researching how to immigrate to Tajikistan. We’d love to buy a small property in the Pamir for example, overlooking snow-peaked mountains. We’ll learn the language and befriend the locals who can teach us their customs. Through intercultural dialogue, we learn about our own worldview. We learn that truth is very subjective.

Finally, what has been your number one travel experience?

Last summer I hitchhiked with a friend from Bulgaria into Turkey, then Georgia and Armenia. When she had to go back to her job in the Netherlands, she flew home. I was left alone in Armenia.

I gathered all my courage and decided to hitchhike back to Bulgaria on my own. It took me 10 days and I covered 2,500km. It went really well. I only met nice people.

To stand there on the side of the road on my own, with a big smile, felt almost symbolic. I felt I was a symbol of trust. People recognised my trust in them and maybe, therefore, never betrayed it.

All day I would hitchhike. Sometimes I’d hide in my tent in the forest at night, but mostly I found protection in a village. I’d get out of the car when I saw a sign on the side of the road indicating a village was coming up and walk the last kilometre.

The people were always very surprised to see me strolling into their village. I asked via Google Translate whether I was allowed to pitch my tent in their orchard. It was never a problem. Often we shared food and drinks. In the morning I’d walk back to the main road and continue. Especially in Turkey, the people were so kind to me. That was very touching.

Ever since I was a child, I dreamed of hitchhiking the world (when I was old enough). Last summer, at age 38, I decided I was old enough. I felt so proud. It was such an adventure. By overcoming my fear, I had grown – like a tree growing towards the light.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…

In Wilder Journeys: True Stories of Nature, Adventure and Connection, Miriam Lancewood and Laurie King have gathered together an extraordinary set of adventurers, nomads and nature lovers who have had profound experiences in nature.