S21 prison processed over 17,000 people for extermination. Today, it is one of Cambodia’s most popular destinations. Is visiting distasteful or important?

There are some sights you likely see only once. Places like Petra, Machu Picchu and Angkor Wat are so grand, exotic and expensive, they are the very definition of a ‘once in a lifetime’ experience.

Other sights are seen once because once is enough; places like Dachau concentration camp in Germany or S21 prison in Cambodia.

It was discomfiting then to find myself at the gates of S21 prison for the second time in five years. My first visit in 2011 had been harrowing enough. We had evaded an overzealous tour guide and journeyed through the former prison alone – a sobering experience I wasn’t sure I wanted to repeat.

Second time around, I arrived in a guided group tour and was interested to see how this would change the experience.

We started in a small room with a stained floor checkered orange and white. A rusty metal bed frame stood at one end – atop it, a pair of shackles and a small box that prisoners used as a toilet. On the wall hung a photograph taken upon the prison’s discovery in 1979. It depicts a rotting corpse chained to the bed in this former torture chamber.

It’s strange how we might read those words – ‘torture chamber’ – in horror film descriptions and imagine secret subterranean cells filled damp and decay. This one sits on an unremarkable city street surrounded by grass, trees and normal suburban life.

The innocuous surroundings hint at the fact that S21 prison wasn’t always a place of horror. It was in fact a high school until it was seized by Pol Pot’s security forces in 1975 and became Security Prison 21, the largest centre of detention and torture in Cambodia.

More than 17,000 people held at S21 were processed for extermination at the killing fields of Choeung Ek, but not before months of torture comprising beatings, electric shocks, searing hot metal instruments, suffocation, waterboarding, hanging, skinning and worse.

So merciless was the regime, the guards were told they had to keep prisoners just-about-alive to continue the torture. If a prisoner died, the overseeing guard would be branded a traitor and face imprisonment themselves.

For those unfamiliar with Pol Pot, it’s worth explaining that over 1.5 million Cambodians died from starvation, execution, disease or overwork under his reign from 1975 to 1979. His party, the Khmer Rouge, first focused their killings on the preceding regime’s soldiers and government officials.

Then, in an attempt to socially engineer a classless peasant society, the party extended killings to academics, doctors, teachers, students, monks and engineers. Later, its paranoia turned on its own ranks and purges throughout the country saw thousands of party activists and their families brought to S21 prison and murdered.

As we tourists stood in that first torture chamber, the photograph on the wall served as a harbinger of the prison’s horrors. This was the point of no return.

Our guide gestured to the photo, pointing out a vulture perched above the body’s decomposing flesh. It’s a ghoulish discovery I missed on my unguided visit years earlier.

There were other changes too. For example, there were now bins dotted around the corners of the complex. On my first visit, I had been angered to see empty coke cans and other trash thoughtlessly flung around the overflowing bin. If we couldn’t expect respect here, then where?

There were also more interpretive signs explaining what happened at S21 prison, no doubt catering to the increasing number of tourists to Cambodia.

Our guide led us through the chambers and into the tiny prison cells which were so small, I couldn’t stretch out my arms.

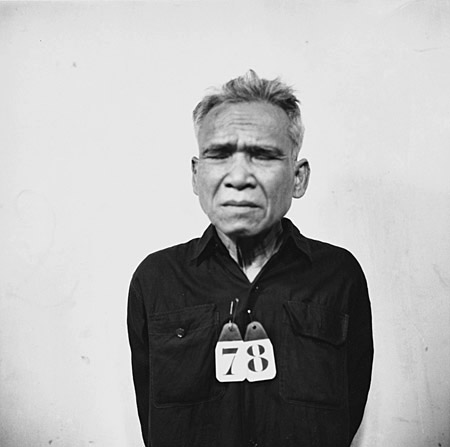

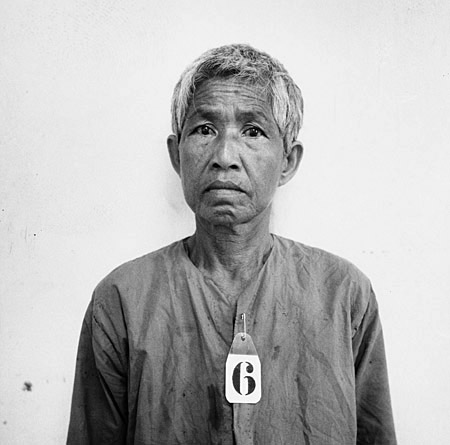

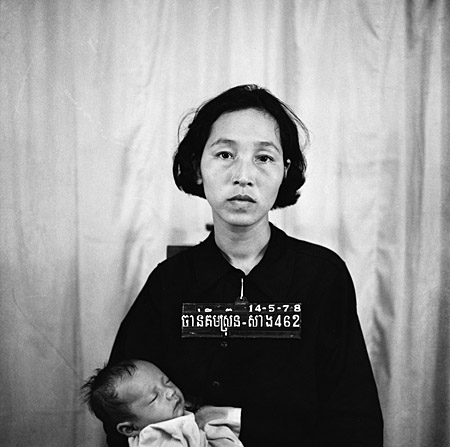

We then moved to what might be the most harrowing of exhibits: rows and rows of prisoner photos. The Khmer Rouge were meticulous in keeping records of their brutality. Each prisoner who passed through S21 prison was photographed – sometimes before and after torture.

As most visitors will note, some prisoners seem terrified, others are angry or defiant, many are neutral in front of the camera, caught in a moment amid one of history’s most horrific ordeals.

Fair Use

Harrowing photos of Khmer Rouge victims at S21 prison

As I walked among the photos, I as a repeat visitor was perhaps best placed to ask: is visiting S21 prison morbid or meaningful? Is it a morally ambiguous cornerstone of dark tourism, or a valuable educational tool?

My conclusion is that it’s a bit of both.

There is death around every corner, in every room. There is no hope amid the horror either; no tales of retribution or justice. Pol Pot reportedly died a peaceful death in the Cambodian jungle and few of his top generals have faced punishment.

So, yes, it’s morbid but it has meaning too. My Eurocentric education taught me all about Nazi Germany but nothing of Pol Pot. Understanding the trials of a faraway land contextualises the history of your own.

It helps you appreciate your place in history and inspires empathy. It also makes you part of the wider consciousness that vows never to let the past become our future.

It’s that last point that I find most significant. On meeting two of the reported seven survivors at the end of the S21 prison circuit, I initially felt a bittersweet sadness. S21 was the worst thing that happened in their lives and now they had set up shop within its walls, reliving the horrors every single day.

But then I remembered Leon Greenman, a WWII survivor and fellow east Londoner whom I met as a schoolgirl. Leon spent time visiting local schools to tell the story of his life in Auschwitz. I remember how he rolled up his sleeve and let us touch his tattoo – number 98288.

Leon was adamant that we ask whatever we wanted no matter how harrowing for him because ‘knowledge is the only way to prevent the past repeating itself’. That afternoon with Leon was stirring in a way months of study could never be.

So, yes, dark tourism can be morbid but if the emphasis is on remembrance and education, then it absolutely, undoubtedly holds value.

S21 prison: the essentials

What: Visiting Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, formerly S21 prison, in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Where: I travelled aboard the Toum Tiou II as part of a Mekong river cruise. If you’ll be staying in Phnom Penh instead, use Booking.com for accommodation.

When: Cambodia is warm all year round. The best time to visit is between November to March when you can enjoy cool, dry days but do note that this is peak season. June to October is hot and potentially wet but is still a good time to visit. Rain tends to fall for a short burst in the afternoon and rarely affects travel plans.

How: I visited on G Adventures’ Mekong River Cruise Adventure, priced from £1,299pp for a 10-day trip from Saigon to Siem Reap. The price includes most meals, activities and a chief experience officer (CEO) throughout. For more information or to book, call 0344 272 2040 or visit gadventures.com.

Note that the prices do not include flights. Vietnam Airlines offers the UK’s only nonstop flights to Vietnam, with daily services from Heathrow Terminal 4 to Hanoi or Saigon. Book via skyscanner.net.

Lonely Planet Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos & Northern Thailand offers a comprehensive guide to the Phnom Penh and the Mekong Delta, ideal for those who want to both explore the top sights and take the road less travelled.