North Sentinel Island is unlike any other place on Earth. Home to a fiercely independent tribe, it is both ferociously dangerous and worryingly fragile

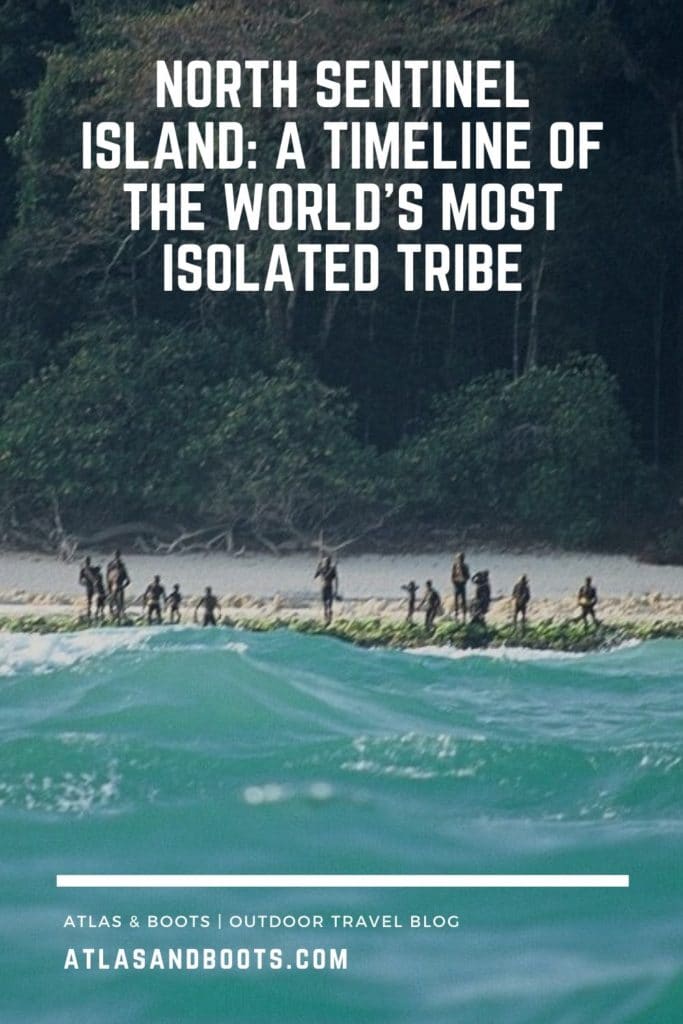

On a map, North Sentinel Island looks like any other idyllic spot in the Indian Ocean. Fringed with beaches and crystal cobalt waters, it lies in the Andaman archipelago of the Bay of Bengal.

North Sentinel, however, is unlike any other island. It has been described as ‘the hardest place in the world to visit’, ‘the world’s most dangerous island’ and home to ‘the most isolated tribe in the world’.

These sensational labels can’t be qualified conclusively, but they do hold some truth. For an estimated 60,000 years, North Sentinel Island has been home to a fiercely independent tribe that has violently rejected contact with the outside world.

The ‘Sentinelis’ have attacked nearly every outsider who has strayed into their territory. In 1896, they stabbed to death an escaped Indian convict who washed up on their shore; in 1974, they greeted a film crew with a hail of arrows; in 2004, a tribesman took aim at an Indian Coast Guard helicopter sent to check for signs of survival post earthquake; in 2006, they killed two fishermen who unwittingly drifted into their waters. When a helicopter was sent to retrieve the bodies, it was greeted by the Sentinelis, weapons in hand.

The Sentinelis’ violent behaviour precludes close observation and, as such, very little is known about them. We know they have weapons (arrows and spears most likely fashioned from wreckage) and that they use fishing nets and basic outrigger canoes. They fish, hunt and collect wild plants, but there is no evidence of agriculture or even methods of making fire. It’s speculated that the Sentinelis wait for lightning and keep the resulting embers burning for as long as possible in a hollowed out tree.

It’s feasible that the Sentinelis are the last people on Earth to remain virtually untouched by modern civilisation – but who are they and why are they so fiercely insular? Should we in the developed world leave them alone – even if it consigns them to eventual doom? What are the ethical implications of contact versus retreat? These are the questions pondered by scientists, researchers, explorers and officials for at least a century. Here, we take a look at the island’s extraordinary timeline.

North Sentinel Island Fact File

Coordinates: 11°33’N 92°14’E.

Location: Andaman Islands, Bay of Bengal. Administered by India since 1947 as part of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Union Territory.

Area: 72km² before the 2004 earthquake (see ‘Topography’ below).

Height: 122m. The 2004 earthquake tilted the tectonic plate under the island, lifting it by another 1-2m.

Topography: Forest surrounded by natural coral reef. Before the 2004 earthquake, reefs extended around the island for 800-1,290m and an islet, Constance Island, was located about 600m off the southeast coastline. After the earthquake, large parts of the coral reefs became exposed, extending the island’s boundaries by as much as 1km on the west and south sides and uniting Constance Island with the main island.

Population: Estimated at 50 to 400 individuals. The 2001 Census of India recorded 39 individuals (21 males and 18 females) while the 2011 Census noted only 15 individuals (12 males and 3 females). However, as the survey was conducted from a distance, there is little chance the numbers are accurate. (Note: the 2021 Census of India has been delayed to late 2024.)

Inhabited since: Estimated 60,000 years. The four Andaman tribes – the Great Andamanese, Onge, Jarawa, and Sentinelese – are known as the Negrito tribes and are of African descent, possibly direct descendants of the first humans out of Africa.

Language: Sentinelese – an unclassified language. Their language is markedly different even from other languages on the Andamans, which suggests that they have remained uncontacted for thousands of years.

1700s

The earliest recorded mention of North Sentinel Island was in 1771 by British surveyor John Ritchie who passed the island on the Diligent, an East India Company hydrographic survey vessel. Much like Magellan and Tierra del Fuego, Ritchie made a note of the island’s ‘multitude of lights’.[1]

NWbW. from the south west corner of Andaman, lies a fine low Island covered with trees; it is a league long, and two miles broad; and if we may judge from the multitude of lights seen upon the shore at night, it is well inhabited; this Island is marked as North Sentinel in the plan; and it is between the Latitudes 11 32′ ‘and 35’ N.

The ship sailed on and nothing was noted of the island for almost a hundred years.

1800s

In March 1867, Jeremiah Homfray, the ‘Officer in Charge of the Andamanese’, journeyed to North Sentinel Island on the trail of some convicts who had escaped from the penal colony at Port Blair.[2]

On approach, Homfray, escorted by police and some Great Andamanese, saw “some ten men on the beach, naked, long haired, and with bows and arrows, shooting fish.”[3][4]

The Sentinelis spotted the boat and hid. The Great Andamanese on board were visibly frightened and warned Homfray of the islanders’ fearsome defensiveness. Homfray astutely decided not to land.

That same year, in the summer of 1867, an Indian merchant ship, the Nineveh, was wrecked on the reef surrounding North Sentinel Island. It’s reported that the 86 surviving passengers and 20 crewmen landed safely on the beach. On the third day, however, they were attacked by the Sentinelis.

The captain later noted: “The savages were perfectly naked, with short hair and red painted noses, and were opening their mouth and making sounds like pa on ough; their arrows appeared to be tipped with iron.”[5]

The captain escaped the attack aboard the ship’s boat and was picked up several days later by a passing brig. A Royal Navy ship was sent to rescue the survivors who managed to ward off the Sentinelis with sticks and stones.

After this, North Sentinel Island lay undisturbed for 13 years.

In January 1880, an armed British expedition managed a successful landing on North Sentinel Island. Led by 20-year-old Maurice Vidal Portman – the Officer in Charge of the Andamanese – the expedition party traipsed through the island in search of the natives. Guided by some Greater Andamanese, they found a network of pathways and a number of freshly abandoned villages.

Portman noted later that the Sentinelis’ “methods of cooking and preparing their food resemble those of the Onges, not those of the aborigines of the Great Andaman”.

In surveying the island’s fertile oil and groves of tropical hardwoods, Portman encountered not a single soul. The Sentinelis had simply disappeared into the forest.

Eventually, after several days of searching, the party discovered six Sentinelis: an elderly couple and four children. They captured the natives and transported them to Port Blair.

Tragically, the six Sentinelis “sickened rapidly, and the old man and his wife died, so the four children were sent back to their home with quantities of presents,” noted Portman.

At the time, he expressed little remorse, instead choosing to note the Sentinelis’ “peculiarly idiotic expression of countenance, and manner of behaving.”

Portman returned to North Sentinel Island on 27th August 1883 after the eruption of Krakatoa in the nearby Sunda Strait was mistaken for gunfire and interpreted as a distress signal. Portman’s search party landed on the island and left gifts before returning to Port Blair.

Portman revisited North Sentinel Island several times between 1885 to 1887 and reportedly grew fond of the natives, noting that “in many ways they closely resemble the average lower class English country schoolboy.”

In later years, Portman addressed a meeting of the Royal Geographic Society in London where he described his interactions with the Andamanese. He admitted that “their association with outsiders has brought them nothing but harm, and it is a matter of great regret to me that such a pleasant race are so rapidly becoming extinct. We could better spare many another.”

In 1896, three escaped Indian convicts fled Port Blair on a makeshift raft and drifted 30 miles to North Sentinel Island. Two of the fugitives drowned on the reefs surrounding the island. The lone survivor made it to the beach but was soon killed by the Sentinelis. A British party later spotted and retrieved his body. It was pierced in several places by arrows and his throat was cut.

After this, North Sentinel Island was left alone for a century. In 1947, India won its independence from Great Britain and gained control of the Andaman Islands, but chose to ignore the Sentinelis for about 20 years.

1960s

In 1967, Indian anthropologist Triloknath Pandit was summoned by the governor of the Andaman islands who was planning a major expedition to North Sentinel Island.

Pandit was offered the opportunity to become the first anthropologist to land on the island, accompanied of course by armed police as well as a number of naval officers, two large patrol boats and inflatable rubber dinghies for navigating the dangerous reef around the island. Pandit accepted a role as manager of the so-called ‘Contact Expeditions’ under his remit as Director of Tribal Welfare.

“There was a feeling that we were trying to establish friendly contact, which would be considered an achievement at the government level,” Pandit said later.[9]

On the first expedition, the Sentinelis retreated into the jungle and there was no contact. The party left gifts of buckets, cloth and candy in the empty huts, but also ‘collected’ a few gifts of their own: bows, arrows, a basket and the painted skull of a wild boar.

The pilfering hints at the undercurrent of one-upmanship that accompanied the Andamanese contact expeditions.

Sita Venkateswar, anthropologist and lecturer at Massey University, told us in 2016: “Remaining hidden is the scrambling, the competition and name dropping involved in ensuring inclusion in the team that is assembled for every ‘gift-dropping’ occasion.”

This jockeying is driven by the possibility of an historic moment emerging from regularly scheduled gift-dropping trip, said Venkateswar: “Any number of ‘first’-time occasions is potentially lurking in the wings. This romance colours all interactions between anthropologists and others as they vie with one another to be included in the team, no matter how many prior trips they may have made when nothing of any ‘significance’ occurred.”

1970s

On 29th March 1970, Pandit and his party found themselves trapped on the reef flats between North Sentinel Island and Constance islet. An eyewitness recorded a series of bizarre events from his vantage point on a boat by the beach.[6]

We were about to return when a couple of natives were seen on the land, apparently keeping a vigil. We approached closer, keeping a safe distance from the shore, when more men came out of cover armed with their usual weapons, threatening to shoot at us. We had taken a few large fish caught during the previous night to offer as an appeasement gift to these people. We exhibited these, with gestures of offering.

Meanwhile, men were converging on the spot from all direction. Some were waist deep in water and threatening to shoot. However, we approached closer and threw a couple of the fish towards them. They fell short of them and were being carried away by the water. This gesture had a mellowing effect on their belligerent mood. Quite a few discarded their weapons and gestured to us to throw the fish.

The women came out of the shade to watch our antics. In their height and stature they were equal to the men except that the lines were softer and they carried no arms … There were 20 children. We approached the coast a little further from them and managed to land a couple of fish on shore. A few men came and picked up the fish. They appeared to be gratified, but there did not seem to be much softening to their hostile attitude.

Again we approached the group. They all began shouting some incomprehensible words. We shouted back and gestured to indicate that we wanted to be friends. The tension did not ease.

At this moment, a strange thing happened – a woman paired off with a warrior and sat on the sand in a passionate embrace. This act was being repeated by other women, each claiming a warrior for herself, a sort of community mating, as it were. Thus did the militant group diminish. This continued for quite some time and when the tempo of this frenzied dance of desire abated, the couples retired into the shade of the jungle.

However, some warriors were still on guard. We got close to the shore and threw some more fish which were immediately retrieved by a few youngsters. It was well past noon and we headed back to the ship.

Anthropologists are unsure how to interpret these events. They are aware of situations in other Andamanese groups when overexcited males were calmed down by the women, but none involved ‘community mating’.

In the absence of reliable information about Sentineli behaviour, there is little point in speculating further.

Later in 1970, a wreck was spotted on a coral reef off the southeast coast of the island. On inspection, it was concluded that the vessel had been lying there for seven or eight months. There was no sign of the crew.

Several years later, in spring 1974, North Sentinel Island was visited by a team of anthropologists filming a documentary Man in Search of Man. The team was accompanied by a National Geographic photographer and armed police officers dressed in jackets with padded armour.

As the boat broke through the reefs, the Sentinelis emerged from the jungle and greeted the visitors with a curtain of arrows. The boat landed further along the coast out of range of the arrows and the police deposited gifts in the sand: coconuts, aluminium cookware, a live pig, a doll and a toy car.

The Sentinelis reacted with another hail of arrows, one of which struck the documentary’s director in the left thigh. It’s said that the offending tribesman withdrew and laughed proudly before taking a seat in the shade while others speared and buried the pig and the doll, taking only the coconuts and cookware.

Later in 1974, an Indian contact party brought three Onge tribesmen to North Sentinel Island in the hopes that they could communicate where the Greater Andamanese could not.[7] Alas, this was of little use: The Onge were too far from the beach to understand what the Sentinelis were shouting in response to their offer of friendship and the anthropologists failed to establish if the Sentinelis understood at least a portion of the Onge’s language

In 1975, Leopold III of Belgium took a tour of the Andamans. Local dignitaries took the former king on an overnight cruise to the waters around North Sentinel Island. The royal party was reportedly faced down by a lone warrior armed with bow and arrow and clad in nothing but a scowl and a few personal decorative items.[7]

In mid 1977, cargo ship MV Rusley ran aground on North Sentinel Island’s coastal reefs. The Sentinelis are known to have scavenged the wreck for iron.[5]

1980s

In summer 1981, cargo ship MV Primrose grounded on the reef surrounding North Sentinel Island. Several days later, the crewmen spotted a number of Sentinelis on the beach carrying spears and arrows.

Shortly after, a wireless operator at the Regent Shipping Company’s offices in Hong Kong received an urgent distress call from the captain of the Primrose.[8]

Wild men, estimate more than 50, carrying various homemade weapons are making two or three wooden boats… Worrying that they will board us at sunset. All crew members’ lives are not guaranteed.

The crew did not receive any support due to a large storm preventing vessels from reaching them. They staved off the Sentinelis with 24-hour guard, flare guns, axes and lengths of pipe.

After a week, on 2nd August 1981, the crew were rescued by a helicopter working under contract for the Indian Oil And Natural Gas Commission.

Captain Robert Fore of the rescue team later shared an account of the rescue. One of his many interesting observations is that the Sentinelis “had not even learned the art of placing feathers on the several foot long arrows they had, which only allowed a practical effective range of perhaps 30 or 40 meters.”

Incidentally, MV Primrose is still visible in satellite images of North Sentinel Island. You may explore the exact coordinates here.

1990s

On 4th January 1991, after 20 years of unsuccessful attempts, an Indian contact expedition established the first peaceful contact with the Sentinelis – since described as the “last first friendly encounter” in history.

Pandit said in a later interview: “That they voluntarily came forward to meet us – it was unbelievable. They must have come to a decision that the time had come. It could not have happened on the spur of the moment.”[9]

The moment was bittersweet, said Pandit: “There was this feeling of sadness also – I did feel it. And there was the feeling that at a larger scale of human history, these people who were holding back, holding on, ultimately had to yield. It’s like an era in history gone. The islands have gone. Until the other day, the Sentinelese were holding the flag, unknown to themselves. They were being heroes. But they have also given up.”

The ‘yielding’, however, was somewhat overstated. Venkateswar told us: “That was very transient. It marked an event that garnered lots of photography and lots of press but it very quickly shifted. It didn’t mean that anything had changed. It didn’t mean that Indians could now safely go over there. The next time anyone attempted to go, there they were lined up along the shore with their arrows and weapons pointed – and that still continues.”

Later in 1991, ship-breakers Mohamed Brothers were given a government permit to salvage metal from the wrecks of the MV Rusley and MV Primrose.

On the workers’ first visit, the Sentinelis came to beach with weapons and started shooting arrows, prompting the salvors’ police escort to fire shots in the air.

The Mohamed Brothers claim that they worked for two months thereafter in peace[5][9], but there have also been unconfirmed reports of fatal clashes.[10]

In September 1991, the Indian government added a 5km exclusion zone around North Sentinel Island under the provisions of the Andaman and Nicobar Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation (ANPATR) – 1956.[11]

The zone is touted as a proactive way to discourage fishermen, poachers and tourists from visiting the island, but some experts remain sceptical.

Venkateswar said: “It looks fantastic on paper, but the exclusion zone doesn’t mean that the chief secretary or a lieutenant governor or someone with clout cannot plan a trip and go to the island and show visitors and friends: ‘Look here, here’s this uncontacted tribe and we’re going to see them.’ Every time there is a VIP or V-VIP visiting the islands, a trip to these areas becomes one of the sights.”

In 1996, several years after the exclusion zone was extended, Indian contact trips to North Sentinel Island finally ceased following a series of fatal encounters with the Jarawa tribe in a similar programme of expeditions.[12]

Since their emergence, the Jarawa have been blighted by alcoholism, a measles epidemic and sexual exploitation, prompting efforts to protect the Sentinelis from a similar fate. Would they now be finally left alone?

Jarawa women being encouraged to dance in exchange for food

2000s

In 2004, three days after the notorious Indian Ocean earthquake, an Indian Coast Guard helicopter flew over North Sentinel Island to search for signs of survival. It was greeted by a lone Sentineli tribesman who took aim at the helicopter. Evidently, the Sentinelis had survived the earthquake and its after-effects, including the tsunami and the lifting of their island.

In 2005, the Andaman and Nicobar Administration stated that they have no intention to interfere again with North Sentinel Island.

“It will now be our avowed policy to minimise unnecessary and inappropriate contact between the primitive tribes,” said Tribal Welfare Secretary, Uddipta Ray.[13]

“Only a few officials in our administration will have access to the aboriginal habitats to protect them from poaching and illegal intrusions by the settlers … We will ensure their food security, the security of their habitats, we will encourage them to pursue their traditional lifestyle, there is no question of imposing any outside culture or beliefs on them,” Ray told the BBC.

On 26th January 2006, two men illegally fishing for mud crabs off North Sentinel Island were killed by the Sentinelis. An Indian Coast Guard helicopter sent to retrieve the bodies was warded off by a customary hail of arrows.

The Andaman Islands’ police chief, Dharmendra Kumar, said: “The tribesmen are out in large numbers. We shall let things cool down and once these tribals move to the island’s other end we will sneak in and bring back the bodies.”[10]

Environmental groups urged the authorities to leave the bodies and respect the exclusion zone around the island.

2010s

On 16th November 2018, 26-year-old American John Allen Chau visited North Sentinel Island illegally and was killed by the Sentinelis. It’s reported that Chau was an evangelical missionary who wished to ‘declare Jesus’ to the tribe.[15][16]

Chau paid local fishermen to ferry him to the island and completed the rest of the journey by kayak. The fishermen said they saw Chau struck by an arrow and later taken into the forest.

Indian police opened a murder case against “unknown tribesmen” and arrested seven people for helping Chau reach the island. Police journeyed to the island, but abandoned their efforts to recover Chau’s body.

Stephen Corry, director of Survival International, said it would be incredibly dangerous for both sides if authorities were to continue their efforts to recover the body: “The risk of a deadly epidemic of flu, measles or other outside disease is very real, and increases with every such contact. Mr Chau’s body should be left alone, as should the Sentinelese.”

2020s

In August 2020, 10 of the 59 surviving members of the Great Andamanese tribe tested positive for Covid-19. It is thought that the Sentinelis remained unaware of the coronavirus pandemic.

In August 2023, The Mission, a documentary exploring the death of John Allen Chau, premiered to critical acclaim.

In November 2023, historian Adam Goodheart – who, by his own admission, “foolishly and illegally” travelled to the coast of North Sentinel 25 years ago – published The Last Island: Discovery, Defiance, and the Most Elusive Tribe on Earth. A work of history as well as travel, it tells the stories of those drawn to North Sentinel’s mystery, from imperial adventurers to modern-day anthropologists. It narrates the tragic stories of other Andaman tribes’ encounters with the outside world and shows how the web of modernity is drawing ever closer to the island’s shores.

The future

Indian officials like to tell the story of how Jacques Cousteau once came to shoot a documentary on the islands and was chased away, or how Claude Lévi-Strauss asked Indira Gandhi to let his students do fieldwork among the Andamanese and she refused.

This makes for good PR, buoyed by the oft-quoted 5km exclusion zone, but as we have heard, small boats of officials can still access the island as can poachers, fishermen and bull-headed tourists.

The Sentinelis have thus far repelled the creep of civilisation unlike the Jarawa who are now faced with infectious diseases to which they have no immunity, sexual exploitation, addiction and pernicious western influence.

The argument that the Sentinelis could benefit from modern medicine and agriculture is a red herring, said Venkateswar: “What are these so-called fruits of civilisation? And what place do tribal groups have in the scheme of things? They are always at the bottom of the pecking order. They are always at the losing end of the interaction.”

Did the Jarawa benefit in any meaningful way from which we can take encouragement?

“There was no benefit to them,” said Venkateswar. “What it did was open up a world that they did not comprehend. What happens as a result of contact is there’s a crack in the existing structure that supported them. As it opens, that crack starts to channel all kinds of things and you can’t control what comes through.

“The Jarawa are not in a position to be able to control what comes through and to take what is good and to discard the chaff, so they’re swallowed up in this huge uncontrollable surge of things that pass through that crack and the crack becomes bigger and engulfs them. It’s like tsunami; it destroys everything in its path.”

She elaborates: “What happens immediately with contact is the use of tobacco, the use of betel nuts, abuse of alcohol and sex. The fruits of civilisation never reach them. There will be several generations of suffering before they are able to get a foothold in the fruits of civilisation and set the terms of it for themselves.”

Corry echoes this sentiment: “The Great Andamanese tribes of India’s Andaman Islands were decimated by disease when the British colonised the islands in the 1800s. The most recent to be pushed into extinction was the Bo tribe, whose last member died [in 2010].[14]

“The only way the Andamanese authorities can prevent the annihilation of another tribe is to ensure North Sentinel Island is protected from outsiders.”

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…

Sources

[1] An Unpublished 18th Century Document about the Andamans, The Indian Antiquary 30:232-238, 1901 (link)

[2] Disciplined Natives: Race, Freedom and Confinement in Colonial India, 2013 (link)

[3] Contemporary Society: Developmental issues, transition, and change, 1997 (link)

[4] The Land of Naked People: Encounters with Stone Age Islanders, 2003 (link)

[5] In the Forest: Visual and Material Worlds of Andamanese History (1858-2006), 2009 (link)

[6] Chapter 12, Lonely Islands: The Andamanese, 1998 (link)

[7] Chapter 8, Lonely Islands: The Andamanese, 1998 (link)

[8] Off the Map: Lost Space, Feral Places and Invisible Cities and What They Tell Us About the World, 2014 (link)

[9] The Last Island of the Savages, 2016 (link)

[10] Stone Age Tribe Kills Fishermen Who Strayed on to Island, The Telegraph, 2006 (link)

[11] The Jarawa Tribal Reserve Dossier, UNESCO, 2010 (link)

[12] India – Andaman Islanders, Minority Rights (link)

[13] Extinction Threat for Andaman Natives, BBC, 2005 (link)

[14] Illegal Fishermen Encroach on World’s Most Isolated Tribe, Survival International, 2014 (link)

[14] Illegal Fishermen Encroach on World’s Most Isolated Tribe, Survival International, 2014 (link)

[15] American killed by isolated tribe on North Sentinel Island in Andamans, The Guardian, 2018 (link)

[16] Man killed on remote Indian island tried to ‘declare Jesus’ to tribe, The Guardian, 2018 (link)