Kia reflects on a visit to Auschwitz from Kraków and defends what some dismiss as problematic tourism

The famous gates of Auschwitz are startling, not because they’re sinister or imposing but the very opposite. Usually depicted in black and white, these gates have featured in myriad Holocaust films and documentaries. Today, however, they’re not in menacing monochrome or veiled in evocative fog. Rather, they’re bathed in sunlight with a blazing blue sky behind.

Inside, there is a symmetry of pretty trees. By the time I arrive at the neat brick buildings, I am thoroughly disoriented. This is not the picture I expected. Instead of squat grey concrete, this could pass for a retirement home – a fact I note uneasily.

The temptation then is to leach our pictures of colour, but that would also leach them of truth. The reality is, of course, that evil can occur in the very midst of beauty. When I ask our educator about the trees, she explains that the SS guards wanted their workplace to be pretty. The ghastly fact silences our group.

There are 30 of us in total, which initially preoccupies me. Peter and I paid extra to join a smaller group but a mixup landed us here. The group is large and unwieldy, and as we weave in and out of buildings, there is little time to pause and reflect.

The educator, however, is brilliant and expertly shepherds us around the grounds. We pause at a map and my quibbles are quickly forgotten. The map shows Auschwitz, Birkenau and Monowitz which, together with a number of sub-camps, are collectively known as the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Auschwitz I, the main camp, was a detention site with prisoner numbers ranging from 15,000 to over 20,000. Birkenau, sometimes known as Auschwitz II, was an extermination camp that held over 90,000 prisoners at times. Monowitz was a labour camp that held 12,000 prisoners. Historians estimate that, together, these camps killed over 1.1 million people, a million of whom were Jews.

It’s hard to fathom these numbers given their magnitude, which is why I would encourage visitors to read around the subject. For me, the most illuminating text was Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man. The Italian chemist was imprisoned at Monowitz and writes about the horrors of the Holocaust in a manner both gentle and urgent, providing essential context for anyone visiting Auschwitz.

Monowitz was also the camp which held Leon Greenman, the Holocaust survivor and activist whom I was privileged to meet as a student. Leon spoke to my secondary school history class about his experiences at Auschwitz. The stories he recollected were haunting but essential. Leon’s goal was to share his account with as many young people as possible for he knew that one day, the world would no longer have a living Holocaust survivor.

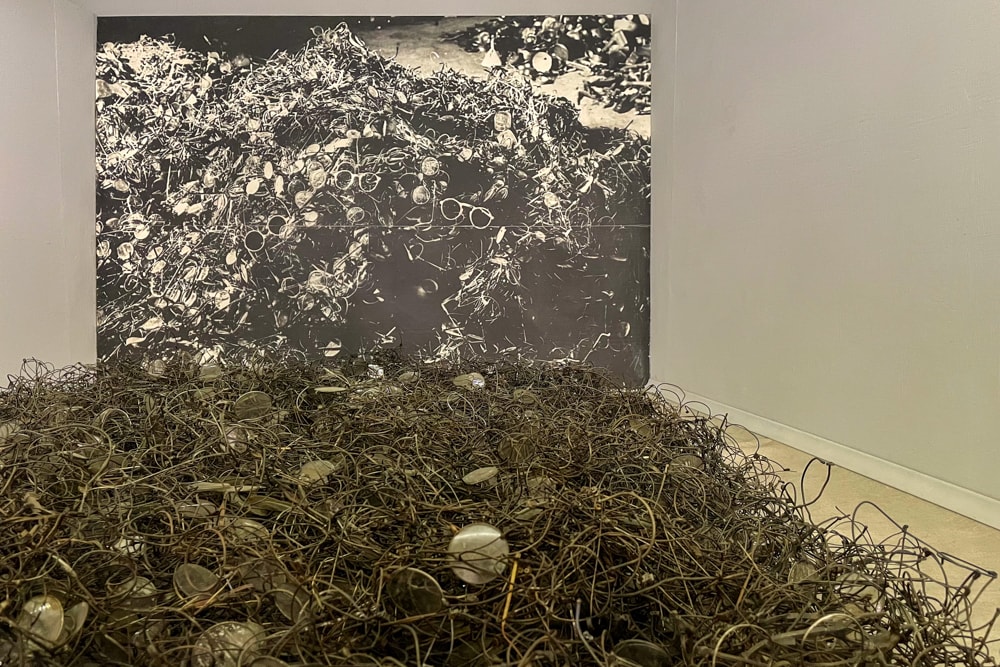

In lieu, the ‘material evidence of crime’ at Auschwitz I will stand testament to the atrocities. Housed in Block 5, this comprises a harrowing set of exhibits: piles of knotted hair shorn from Holocaust victims; a mass of glasses, their stems forever tangled; thousands of mismatched shoes; hundreds of prosthesis taken from prisoners with disabilities; and 3,800 suitcases, 2,100 of which bear the names of their owners.

Everyday items are rendered devastating: a bowl packed for a future that never transpired, shaving brushes, a pocket watch. Their owners trusted the system of “resettlement”, which is one of the many unbearable details of the Holocaust. There are accounts of SS guards feigning shock at the conditions in which their victims were transported as if it were an aberration; of gently assisting the sick onto the trucks that would take them to their killing.

Among the sobering sites in Auschwitz are the notorious gas chambers, the ‘wall of death’ where thousands of prisoners were killed by firing squad, and roll call square where the daily headcount could last for hours (the longest recorded was 19 hours).

It’s hearing about the sonderkommando that makes me most emotional. These prisoners were forced to burn the bodies of gas chamber victims. Our educator explains that, occasionally, the sonderkommando would find a family member among the corpses.

Another sobering moment comes in the long corridor of registration photographs, which were taken when prisoners first arrived. I notice a pair of twins, Maria and Czesława Krajewska who were 15 years old when they arrived. On reading the dates beneath their photos, I realise that the sisters died before their 16th birthday. Czesława survived exactly two months longer than Maria.

Next, we approach the infamous rail tracks of Birkenau, which lies two miles from Auschwitz I. Birkenau is 20 times the size of the main camp and was largely destroyed by their Nazis in their efforts to cover up their crimes.

The remnants – a vast field of chimney stacks, the rubble of a gas chamber, and old wooden barracks – are a chilling reminder of the mass extermination that took place there. But it’s not just the means of death but also the means of living that has the power to horrify here.

Inside one of the barracks, our educator asks why we think prisoners preferred the top bunks. The answer is appalling: prisoners’ chronic diahorrea would filter through the wooden slats to the bunks below.

It’s details like this that leads some pundits to question if this sort of education veers into obscenity. You will find no similar hand-wringing here. To me, it is clear that we have to remember, and that includes all the horrors and indignities.

Leon Greenman worried that the world would forget. He himself tried to move on until he heard Colin Jordan, a leading figure in post-war neo-Nazism, address a rally in Trafalgar Square in 1962. Leon became determined to tell his story and bear witness to the Holocaust.

The ideology that allowed the Holocaust to happen is not consigned to a past century. In 2009, the sign at the gates of Auschwitz bearing the Nazi slogan “Arbeit macht frei” (“Work sets you free”) was stolen by a neo-Nazi. Populism is on the rise and genocide has been reported in Myanmar, China and several other countries.

With this in mind, the invocation to ‘never forget’ isn’t tired or irksome as some have suggested but a simple and effective plea. Soon, there will be no living Holocaust survivors, which is why we have a responsibility to learn about these atrocities – and why we must remember.

Visiting Auschwitz from Kraków: the essentials

What: Visiting Auschwitz from Kraków, Poland.

Where: In Kraków, we stayed at H15 Luxury Palace hotel located in the heart of Kraków’s Old Town, just 200m from Rynek Główny (Central Square). We were picked up from right outside the hotel.

When: To avoid the summer crowds, the shoulder seasons of spring (March to April) and autumn (September to October) are best for visiting Auschwitz from Kraków.

How: You can visit Auschwitz from Kraków on a full day tour. This is the easiest option but be aware that you may be placed in a group of 30 people, which isn’t ideal.

Individuals can visit without a guide at certain times of the year. Select ‘visit for individuals’ on the ticket site, select a date, and scroll to the bottom of the next page as these slots are usually offered at the end of the day. Book your tickets in advance, ideally a few weeks before you plan to visit.

Public buses run to Auschwitz from Kraków. Check getting to the museum for the latest schedules and information.

We visited Kraków by train with our Interrail Global Pass.